High-Altitude Oxygen Risk Calculator

Calculate Your Oxygen Risk

Important Safety Notes

Never sleep at altitude with sedatives. Oxygen saturation below 85% requires immediate descent. Use a pulse oximeter if possible.

Estimated Oxygen Saturation

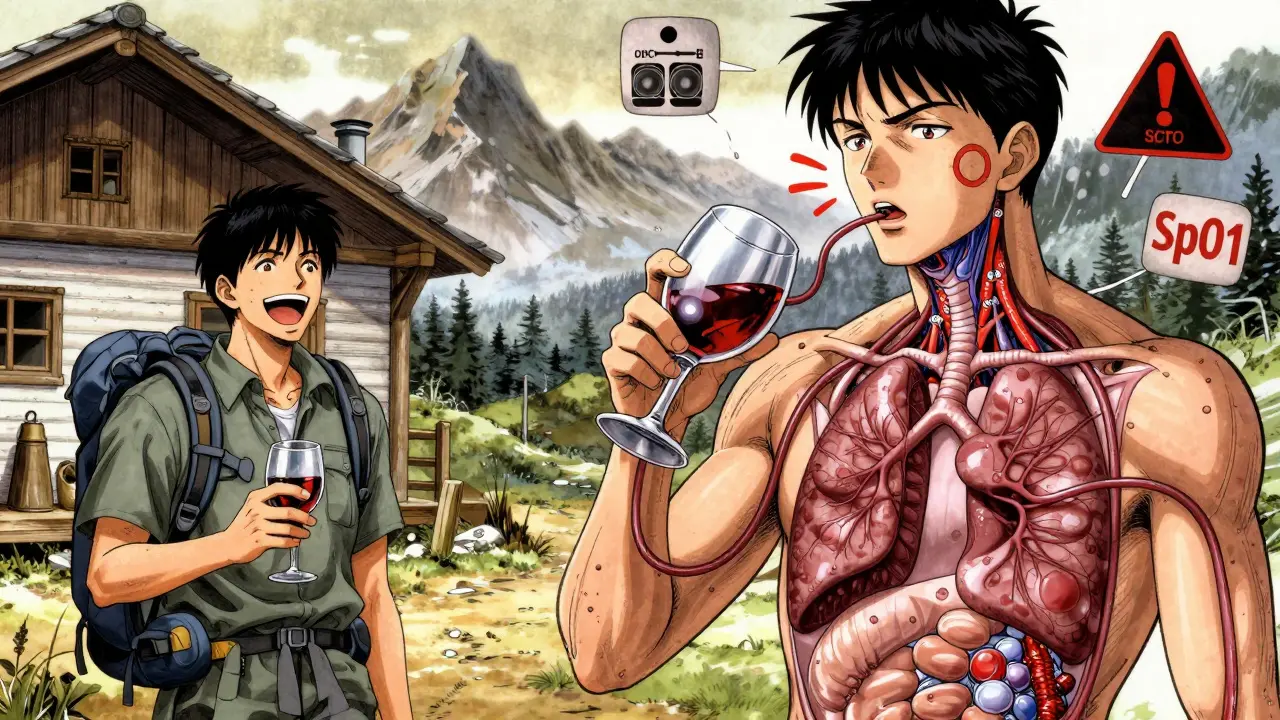

Calculate your riskGoing high up in the mountains can be thrilling - clear air, stunning views, and that sense of adventure. But if you're thinking about taking a sleeping pill, a glass of wine, or even a benzodiazepine to help you rest, you're putting yourself at serious risk. The problem isn't just that you might not sleep well - it's that sedatives can dangerously slow your breathing when oxygen is already scarce.

Why Altitude Changes Everything

At elevations above 2,500 meters (about 8,200 feet), the air doesn't just feel thinner - it literally has less oxygen. For every 1,000 meters you climb, oxygen availability drops by roughly 6.5%. At 4,500 meters (14,800 feet), you're breathing air with only about half the oxygen you get at sea level. Your body knows this. It tries to compensate by making you breathe faster and deeper, especially at night. This is called the hypoxic ventilatory response, and it's your lifeline.But here's the catch: many common sedatives - including alcohol, benzodiazepines like diazepam or lorazepam, and opioids - blunt that response. They tell your brain to slow down breathing. At altitude, that’s like turning off your oxygen alarm system. Studies show that even a single drink can reduce your body’s ability to respond to low oxygen by 25%. Benzodiazepines can cut ventilation by 15-30%. The result? Oxygen saturation plummets. People sleeping at 4,000 meters with sedatives have been documented with SpO2 levels dropping below 76% - a level that can trigger organ stress and even life-threatening complications.

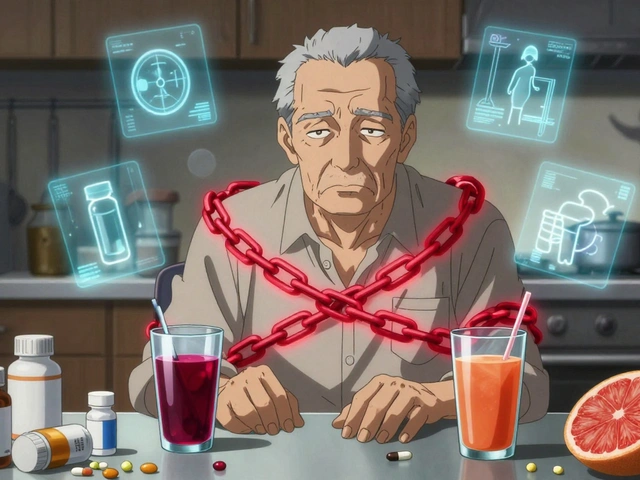

What Sedatives Are Most Dangerous?

Not all sleep aids are created equal. Some are far riskier than others at altitude.- Alcohol: The most common mistake. It doesn’t just make you drowsy - it suppresses your breathing reflex. A 1998 study found alcohol lowers nighttime oxygen levels by 5-10 percentage points. One traveler in Nepal reported his headache turned into vomiting after just two beers at 3,500 meters.

- Benzodiazepines (diazepam, lorazepam, alprazolam): These are prescribed for anxiety or insomnia, but they’re a bad idea at altitude. A 2001 study showed diazepam reduces the hypoxic ventilatory response by 28%. Users on forums have reported SpO2 drops from 88% to 76% after taking even small doses.

- Opioids (codeine, oxycodone, morphine): These are the worst. Even therapeutic doses at 4,500 meters have caused oxygen saturation to fall below 80%. In remote areas, where medical help is hours away, this can be fatal.

- Zolpidem (Ambien): The only exception with some data behind it. A 2017 study found zolpidem 5 mg caused only a 2.3% drop in oxygen saturation at 3,500 meters. The CDC says it’s “generally safe” - but only if you wait at least 8 hours before hiking or driving. Even then, some users report dangerous drops, so caution is critical.

- Melatonin: No evidence it harms breathing. Small studies suggest it may even help improve sleep without affecting oxygen. The CDC doesn’t have enough data to officially recommend it, but many climbers use 1-3 mg with no issues.

What the Experts Say - And Why You Should Listen

This isn’t just a theory. Leading medical groups all agree:- The CDC Yellow Book 2024 says: “Avoid respiratory depressants such as alcohol and opiates.”

- Dr. Peter Hackett, director of the Institute for Altitude Medicine, states: “Any medication that depresses respiration is contraindicated above 2,500 meters.”

- The Cleveland Clinic warns: “Do not take sedatives or sleeping pills. They interfere with how your body adapts.”

- Healthdirect Australia advises: “Do not take sedatives or sleeping pills at high altitude.”

- The Wilderness Medical Society updated its guidelines in April 2024, reinforcing that sedatives can worsen periodic breathing and trigger acute mountain sickness.

These aren’t vague opinions. They’re based on decades of research, clinical cases, and real-world data from climbers, hikers, and expedition teams. When you ignore them, you’re not just risking a bad night’s sleep - you’re risking your body’s ability to survive.

Altitude Sickness Isn’t Just a Headache

Many people think altitude sickness is just a headache or nausea. But it’s more complex. At 8,000 feet or higher, 15-40% of travelers develop acute mountain sickness (AMS). Symptoms include dizziness, fatigue, nausea, and trouble sleeping. But if your breathing is suppressed by sedatives, AMS can quickly turn into high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) or high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE) - two life-threatening conditions.One Reddit user at 4,000 meters took a single 5 mg zolpidem and saw his SpO2 drop to 79%. He didn’t feel sick until the next morning - by then, his lungs were starting to fill with fluid. He was lucky he descended quickly. Others aren’t so fortunate.

Alcohol makes AMS worse. A 2021 survey of 1,247 trekkers found that 68% who drank alcohol during acclimatization reported worse symptoms than those who didn’t. That’s not coincidence - it’s physiology.

What Should You Do Instead?

You don’t need sedatives to sleep at altitude. Here’s what works:- Acclimatize slowly: Give your body 24-48 hours to adjust before going above 2,500 meters. Don’t fly straight from sea level to 4,000 meters and expect to feel fine.

- Use acetazolamide: This prescription drug (125 mg twice daily) helps your body adjust faster. It actually improves oxygen levels at night and reduces the weird breathing patterns that make sleep feel broken.

- Try melatonin: 0.5-3 mg an hour before bed. No respiratory depression. No hangover. Just better sleep.

- Stay hydrated: Dehydration worsens altitude symptoms. Drink water like it’s your job.

- Get a pulse oximeter: Portable devices cost under $50. Monitor your oxygen saturation. If it drops below 85% while resting, it’s a red flag.

- Avoid caffeine and alcohol: Both dehydrate you and interfere with your body’s natural adaptation.

The Bigger Picture: Why People Still Take the Risk

Despite all the warnings, 41% of high-altitude travelers still drink alcohol during acclimatization. Eight percent use prescription sedatives. Why? Because they don’t know better. Or they think, “I’ve taken this pill before - it’s fine.”But altitude isn’t like driving or flying. Your body doesn’t adapt overnight. And sedatives don’t just make you sleepy - they disable your body’s most important survival mechanism. The market for high-altitude travel is growing - over 15 million people travel to elevations above 2,500 meters annually. Yet most travel clinics still give generic advice. Few mention oxygen monitors. Few warn about zolpidem’s hidden risks.

Professional guides know better. 89% of IFMGA-certified guides enforce strict no-sedative policies. They’ve seen what happens when people ignore the rules.

Final Advice: Don’t Gamble With Your Breathing

If you’re heading to the mountains, plan ahead. Talk to a travel medicine specialist at least 4-6 weeks before departure. Don’t rely on your family doctor - they may not know altitude medicine. Bring a pulse oximeter. Skip the wine. Skip the sleeping pills. Use melatonin if you need help sleeping. Take acetazolamide if you’re at risk for altitude sickness.Your body is smart. It knows how to adapt - if you let it. Sedatives don’t just ruin your sleep. They silence the signal your body needs to survive. At high altitude, that’s not a risk worth taking.

Can I take melatonin at high altitude?

Yes, melatonin is considered safe at high altitude. Studies show it doesn’t suppress breathing and may even help improve sleep and oxygen levels. Doses of 0.5-5 mg taken an hour before bed are commonly used by climbers with no reported respiratory issues. While the CDC hasn’t formally endorsed it for altitude, there’s no evidence of harm, and many travelers find it effective.

Is zolpidem (Ambien) safe for altitude?

Zolpidem 5 mg has been studied at 3,500 meters and caused only a 2.3% drop in oxygen saturation - much lower than benzodiazepines. The CDC says it’s “generally safe” if you allow 8 hours for the effects to wear off before physical activity. But some users still report dangerous drops in oxygen. Use it only if absolutely necessary, and never if you’re already feeling symptoms of altitude sickness.

Why is alcohol so dangerous at high altitude?

Alcohol reduces your body’s hypoxic ventilatory response by up to 25%, meaning you breathe less deeply when you need oxygen most. It also dehydrates you and worsens symptoms of acute mountain sickness. Studies show 68% of trekkers who drank alcohol reported worse symptoms than those who didn’t. Even one drink can make a difference at 4,000 meters.

What should I do if I start feeling dizzy or short of breath after taking a sedative?

Descend immediately - at least 500 to 1,000 meters. Don’t wait. Oxygen levels can drop rapidly. If you have a pulse oximeter and your SpO2 is below 80%, seek medical help. Sedatives can mask symptoms until it’s too late. Your priority is getting to lower altitude, not waiting to see if it gets better.

Are there any legal restrictions on sedatives at high-altitude destinations?

No country bans sedatives specifically for altitude use. However, many popular destinations - like Nepal, Peru, and Bolivia - include warnings in tourist materials about alcohol and sleeping pills. Local guides and clinics often advise against them, even if it’s not legally enforced. The risk is physiological, not legal.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published.

8 Comments

Been up in the Rockies with a bad cold and zero sleep meds. Turned out better than I expected. Body figures it out if you just stop fighting it. No wine, no pills, just tea and patience.

The data presented here is rigorously supported by clinical studies, particularly the 2001 study on diazepam’s impact on hypoxic ventilatory response and the 2017 zolpidem trial at 3,500 meters. The CDC’s position is not anecdotal-it is evidence-based, and ignoring it constitutes a preventable medical risk. Melatonin, as noted, remains the only non-depressant option with consistent safety profiles across populations.

One guy I knew took Ambien at 4,200 meters… woke up blue. Not joking. Had to be helicoptered out. His wife cried for weeks. I don’t care how tired you are. Don’t. Do. It.

It is an undeniable and scientifically verifiable fact that the administration of respiratory depressants at elevations exceeding 2,500 meters constitutes a gross violation of physiological safety protocols. The Wilderness Medical Society, the CDC, and the Institute for Altitude Medicine have issued unambiguous directives. To disregard these is not merely irresponsible-it is reckless endangerment. The notion that ‘I’ve taken this before’ is a dangerous fallacy rooted in cognitive bias and a lack of scientific literacy.

We think of altitude as a physical challenge, but it’s really a metaphysical test. Your body doesn’t just need oxygen-it needs surrender. Sedatives are the ego’s last stand against nature’s rhythm. You’re not sleeping-you’re numbing your way out of evolution’s demand. The mountain doesn’t care if you’re anxious. It just wants you to breathe. And if you can’t? Then you’re not ready. Not because you’re weak. But because you’re still trying to control what can only be surrendered to.

They say alcohol bad but what about the big pharma? Who made these pills? Who got rich off your fear of sleep? They tell you melatonin is safe but they dont tell you it comes from china. You think they care if you live? They care if you buy. Always check the label. Always question. This is all a trap to sell you more pills.

Man, I’ve guided trekkers in the Himalayas for over a decade. The ones who come in with a suitcase full of Ambien and wine? They’re the ones we have to watch like hawks. The ones who show up with a thermos of ginger tea, a pulse ox, and a quiet mind? They summit. It’s not about the gear-it’s about the mindset. You don’t conquer altitude. You listen to it. And if you’re too wired to hear it? Then maybe you need to sit still for a while before you even lace up your boots.

bro the body dont need no pills to chill. i went to simien mountains with no sleep aid, just water and patience. my ox went down to 82 but i just sat there breathing slow like my grandpa taught me. no meds, no drama. the mountain dont lie. if you feel like u need somethin to sleep… u already in trouble. just breathe. trust the process. we all got lungs. use em.