When a pregnant person takes a pill, gets an injection, or uses a patch, it’s easy to assume the medicine stays where it’s meant to - in their body. But the truth is more complicated. Many medications don’t stop at the mother. They cross the placenta, entering the bloodstream of the developing fetus. This isn’t always dangerous, but it can be. Understanding how and why this happens is critical for anyone managing health during pregnancy.

The Placenta Isn’t a Wall - It’s a Gatekeeper

The placenta is often called a barrier, but that’s misleading. It’s not a solid wall blocking everything. It’s a living, breathing organ, about the size of a dinner plate and weighing half a kilogram at full term. Its job? To let oxygen and nutrients in, and waste out. And yes - sometimes, it lets drugs slip through too.

Early on, scientists thought the placenta protected the baby like a shield. That changed in the late 1950s when thousands of babies were born with severe limb defects after their mothers took thalidomide for morning sickness. The drug crossed the placenta easily. That tragedy forced medicine to rethink everything. Today, we know the placenta is selective, not foolproof. Some drugs pass through quickly. Others barely make it. And the reasons why matter deeply.

How Do Drugs Actually Get Through?

There are four main ways medications cross the placenta: passive diffusion, active transport, endocytosis, and facilitated diffusion. Most drugs rely on passive diffusion - the simplest route. If a drug is small, fat-soluble, and not stuck to proteins in the blood, it slips through the placental membranes like water through a sieve.

For example, alcohol (molecular weight 46) and nicotine (162) are tiny and dissolve easily in fat. They reach fetal levels nearly equal to the mother’s within an hour. Same with many antidepressants like sertraline. Studies show cord blood levels are 80-100% of maternal levels. That’s why some newborns experience jitteriness, feeding problems, or breathing issues after birth - a condition called neonatal adaptation syndrome.

But not all drugs move this way. Large molecules like insulin (weight 5,808) barely cross. Less than 0.1% of the mother’s dose reaches the baby. Same with many antibiotics and chemotherapy drugs - if they’re too big or too water-soluble, they get stuck.

Then there are the gatekeepers: transport proteins. The placenta has its own version of bouncers - proteins like P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and BCRP. These actively pump drugs back toward the mother’s side. HIV medications like lopinavir and saquinavir are good examples. Even though they’re small enough to passively diffuse, P-gp kicks them out. In lab tests, blocking P-gp made fetal exposure jump by nearly 2.5 times. That’s why some antiretrovirals are chosen over others during pregnancy - not just for effectiveness, but for how much the placenta lets through.

Timing Matters - First Trimester Is Riskier

Not all pregnancies are the same when it comes to drug exposure. The placenta changes as the baby grows. In the first trimester, it’s still developing. Tight junctions between cells aren’t fully formed. Efflux pumps like P-gp aren’t working at full strength. That means more drugs can slip through.

Studies show the placenta is 2-3 times more permeable early on than at term. That’s why the first 12 weeks are the most sensitive for birth defects. A drug that might be safe later could cause serious harm now. Antiepileptic drugs like valproic acid are a clear example. When taken in early pregnancy, they’re linked to a 10-11% risk of major birth defects - nearly five times higher than the general population. That’s why doctors often switch women to safer alternatives before conception.

By the third trimester, the placenta is more protective. But that doesn’t mean drugs are harmless. Some, like opioids, still cross easily. Methadone and buprenorphine reach fetal levels at 65-75% of the mother’s concentration. That’s why so many babies born to mothers on these drugs develop neonatal abstinence syndrome - they’re physically dependent and go through withdrawal after birth.

What Makes a Drug More Likely to Cross?

It’s not random. Certain chemical traits make a drug more likely to reach the fetus:

- Molecular weight under 500 Da - drugs lighter than this cross far more easily. Over 70% of small-molecule drugs fall into this range.

- High lipid solubility (log P > 2) - fats dissolve in fat. Drugs that love fat get through faster. This increases transfer by 50-60%.

- Low protein binding - only the free, unbound part of a drug can cross. Warfarin is 99% bound to proteins - so very little gets through, even though it’s small and fat-soluble.

- Non-ionized at blood pH - drugs that are neutral (not charged) move more easily. Ionized drugs, like many antibiotics, get blocked.

These rules help doctors choose safer options. For example, if a pregnant person needs an antibiotic, amoxicillin (small, low protein binding) is preferred over doxycycline (which binds strongly to fetal bones). If they need pain relief, acetaminophen crosses minimally and is preferred over NSAIDs like ibuprofen, which can reduce amniotic fluid and affect fetal heart development after 20 weeks.

What About Prescription Drugs and Supplements?

Many people assume if a drug is prescribed, it’s safe in pregnancy. That’s not true. Even common medications carry risks.

SSRIs like sertraline and fluoxetine are widely used for depression in pregnancy. About 30% of babies exposed to them show mild symptoms after birth - irritability, tremors, poor feeding. These usually fade within days, but they’re still concerning. The risk of untreated depression must be weighed against this.

Antiepileptic drugs are another big concern. Phenobarbital and valproic acid cross easily and are linked to cognitive delays and physical malformations. Levetiracetam and lamotrigine are now preferred because they cross less and have better safety records.

Even over-the-counter supplements can be risky. High-dose vitamin A (retinol) is a known teratogen. Herbal products like black cohosh or dong quai have no safety data in pregnancy but are often taken without warning. The FDA doesn’t regulate herbs the same way as drugs - so there’s no guarantee of what’s inside or how much crosses the placenta.

What’s Being Done to Improve Safety?

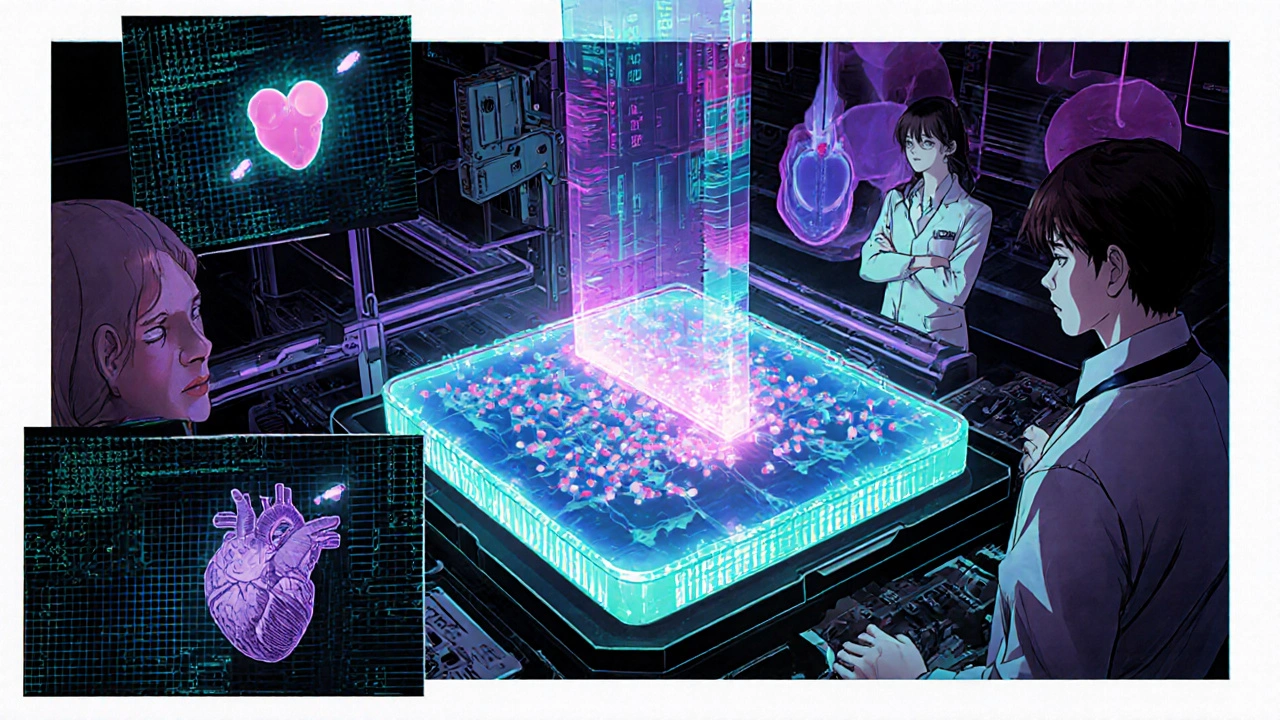

Regulations have changed. Since 2015, the FDA requires drug makers to include data on placental transfer in new applications. No more guessing. Companies now use advanced models - like placenta-on-a-chip - to test how drugs move before they ever reach pregnant women.

These tiny devices mimic the placenta’s structure and function. One study showed glyburide (a diabetes drug) transfer rates matched real placenta tests within 1%. That’s huge. Researchers are also using radioactive tracers to watch drugs move in real time inside the placenta - no animals, no guesswork.

But gaps remain. Over 45% of prescription drugs still lack clear safety data in pregnancy. And most research is done on full-term placentas - even though the most critical development happens early. Experts like Dr. Carolyn Coyne point out that we’re still flying blind in the first trimester.

Meanwhile, new tech is emerging. Nanoparticles designed to target the placenta for fetal therapy are being tested. But there’s a catch: if they get stuck in the placenta, they could cause inflammation or damage. The $285 million market in placental-targeted delivery is growing fast - but safety is still the biggest hurdle.

What Should You Do?

If you’re pregnant or planning to be:

- Never stop or start a medication without talking to your doctor - even if it’s ‘just’ a supplement.

- Ask: ‘Does this cross the placenta? What’s the evidence?’

- For chronic conditions like epilepsy, depression, or asthma, work with your doctor to switch to the safest option before conception.

- Use tools like the FDA’s Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule to check updated drug info.

- Be cautious with OTC meds and herbs. Just because it’s ‘natural’ doesn’t mean it’s safe.

There’s no perfect answer. Sometimes the risk of not treating a condition - like high blood pressure or seizures - is greater than the risk of the medication. That’s why personalized care matters. The goal isn’t to avoid all drugs. It’s to choose the right ones, at the right time, in the right dose.

What’s Next?

Research is moving fast. Phase I trials for P-gp modulators - drugs that can temporarily block placental pumps to help deliver medicine to the fetus - are set to begin in late 2024. This could one day help treat fetal conditions like anemia or infections without harming the mother.

But until then, the best tool we have is knowledge. The placenta isn’t a wall. It’s a filter. And understanding how it works helps protect both mother and baby - not by avoiding all drugs, but by choosing the right ones wisely.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published.

10 Comments

Wow, this is one of those posts that makes you realize how little we actually know about what’s happening inside the body during pregnancy. I had no idea the placenta was so selective-like a bouncer with a PhD in pharmacology. The part about P-glycoprotein kicking drugs back out? Mind-blowing. And the fact that some meds cross 100% into fetal blood? That’s not just science-it’s life-altering. I’m going to print this out and give it to my OB-GYN next visit.

So let me get this straight-we’re trusting a biological filter that’s been studied since the 1950s, with 45% of drugs still having zero data, and you want me to ‘just talk to my doctor’? Cool. I’ll just ask my doctor to magically know what the placenta thinks about my Adderall. Right.

I’m a nurse who’s worked in maternal-fetal care for 12 years, and this post nailed it. The fear around meds during pregnancy is real-but so is the fear of uncontrolled hypertension or seizures. We don’t say ‘avoid all drugs.’ We say ‘choose the right one.’ That’s the difference between panic and care. Thank you for writing this with so much nuance.

Let me tell you something-I’ve been following placental research since the early 2010s, and the shift from ‘it’s a barrier’ to ‘it’s a dynamic, regulated transporter’ has been nothing short of revolutionary. And now we’ve got placenta-on-a-chip tech that can simulate transfer rates within 1% accuracy? That’s like going from a horse-drawn cart to a Tesla in 20 years. The real tragedy isn’t that we didn’t know before-it’s that we still don’t know enough about the first trimester, when the baby’s organs are forming, and the placenta’s still learning its job. We’re treating pregnancy like a medical condition to be managed, not a physiological miracle to be understood-and that’s why so many women feel left in the dark. We need more funding, more research, and more honesty-not just guidelines that say ‘use with caution’ and call it a day.

So… what you’re saying is, if I take a Tylenol, my baby gets 90% of it? Cool. I’ll just keep doing that then. 😴

The assertion that molecular weight under 500 Da facilitates placental transfer is scientifically accurate; however, lipid solubility (log P > 2) is not merely a correlational factor-it is a primary determinant of passive diffusion kinetics. Furthermore, the assertion that non-ionized compounds cross more readily is contingent upon the pH partition hypothesis, which assumes thermodynamic equilibrium, a condition rarely achieved in vivo due to placental perfusion gradients. The cited data on sertraline cord blood levels (80–100%) are consistent with recent meta-analyses (e.g., Einarson et al., 2022), but the clinical significance of neonatal adaptation syndrome remains underreported in observational studies due to ascertainment bias.

This is one of those posts that doesn’t just inform-it reassures. I’ve been terrified to take my antidepressant during pregnancy, thinking I was putting my baby at risk. But reading how doctors weigh the risks of untreated depression against the low transfer of sertraline? That helped me breathe. I wish more medical content felt this balanced. Thank you.

okay so i just found out my prenatal vitamin has like 1000% of the daily vit a and now i’m panicking because i read somewhere that too much retinol causes birth defects and i’ve been taking it since i got a positive test and now i’m crying in my car at the gas station and my toddler is asking why mommy is crying and i don’t know what to do???

The clinical implications of placental drug transfer are profound and necessitate a multidisciplinary approach. Obstetricians, pharmacists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists must collaborate to ensure that medication regimens are individualized, evidence-based, and continuously reassessed throughout gestation. The emergence of placental transport models represents a paradigm shift, yet clinical translation remains slow due to regulatory inertia and insufficient provider education. Standardized, accessible decision-support tools-integrated into EHRs-are urgently needed to bridge the gap between research and practice.

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me that my 23-week ultrasound showed a healthy baby, but I’ve been secretly taking that herbal tea for ‘calmness’ because my sister said it’s ‘all natural,’ and now I’m a monster because some scientist says it might cross the placenta? I’ve been doing everything right-I drank no alcohol, ate organic, meditated, avoided caffeine, and now you’re going to tell me that my chamomile tea is a ticking time bomb? I’m not even mad-I’m just… heartbroken. Like, I’ve been trying so hard and now I find out I’ve been failing in ways no one ever warned me about? And the worst part? No one’s going to tell me what’s safe. Everyone just says ‘ask your doctor’-but my doctor doesn’t even know about herbs. So now I’m just supposed to live in fear? Great. Thanks for the guilt trip.