Primidone Therapeutic Monitoring Calculator

Estimate Phenobarbital Levels

Primidone converts to phenobarbital in the liver. This calculator estimates phenobarbital levels based on primidone dosage, helping assess if you're in the therapeutic range (10-20 µg/mL).

Estimated Phenobarbital Level

10-20 µg/mLNote: Primidone converts to phenobarbital at approximately 30-40% rate

Dosing Guidance:

Below 10 µg/mL:

Consider increasing primidone dose

Above 20 µg/mL:

Consider reducing primidone dose

Why Primidone Matters in Epilepsy Care

When a seizure strikes, the brain’s electrical storm needs a reliable calm‑down agent. Primidone has been serving that role for decades, yet many still wonder what makes it tick. This article breaks down the chemistry, the biology, and the clinical facts behind its anticonvulsant power, so you can see why doctors keep it on the formulary.

What is Primidone?

Primidone is a synthetic heterocyclic compound first approved in the 1950s for seizure control. It belongs to the class of barbiturate‑related agents, but unlike classic barbiturates it is used primarily for chronic epilepsy rather than acute sedation.

How Primidone Stops Seizures: The Core Mechanisms

Two biochemical pathways dominate its anticonvulsant action:

- Enhancement of Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)‑mediated inhibition.

- Blockade of Voltage‑gated sodium channels that fire the neuronal avalanche.

At the synapse, Primidone (and its active metabolite) increase the opening time of GABAA receptors, letting more chloride ions flow in and hyper‑polarizing the neuron. This makes it harder for an incoming excitatory pulse to push the cell to threshold.

Simultaneously, the drug binds to the inactivated state of sodium channels, stabilising them and preventing the rapid depolarisation that fuels seizure propagation. The combined effect is a double‑lock on electrical over‑activity.

From Pro‑Drug to Active Metabolite: The Metabolism Story

Primidone isn’t a full‑fledged blocker on its own; instead it’s a pro‑drug that converts in the liver into Phenobarbital. The transformation is driven by Cytochrome P450 enzymes, chiefly CYP2C19 and CYP2C9. Roughly 30‑40% of a dose becomes phenobarbital within a few hours, while the remainder stays as the parent compound.

This metabolic partnership explains two clinical quirks:

- Primidone’s therapeutic levels are reached slower than many newer antiseizure drugs, often requiring a 2‑week titration.

- Its half‑life is prolonged (up to 100 hours) because phenobarbital adds its own long elimination phase.

Understanding this conversion helps clinicians anticipate drug interactions. For instance, strong CYP2C19 inhibitors (like omeprazole) can lower phenobarbital formation, potentially reducing efficacy.

Pharmacokinetics at a Glance

Key numbers for the average adult:

- Absorption: Almost complete within 2 h.

- Peak plasma: 1‑3 h for Primidone, 8‑12 h for phenobarbital.

- Half‑life: 5‑10 h (Primidone), 70‑140 h (phenobarbital).

- Protein binding: 70‑80 % (Primidone), 45‑55 % (phenobarbital).

Because the metabolite contributes heavily to seizure control, clinicians often monitor total phenobarbital levels rather than Primidone alone.

Clinical Efficacy: Which Seizures Does It Tame?

Primidone shines in several seizure categories:

- Generalised tonic‑clonic seizures - classic “grand mal” episodes.

- Myoclonic seizures - brief, shock‑like jerks.

- Partial seizures with secondary generalisation.

Randomised trials from the 1970s to early 2000s consistently show a 45‑55 % responder rate (≥50 % seizure reduction) as monotherapy for newly diagnosed patients. When paired with other agents, the synergistic effect can push responder rates above 70 %.

How Does Primidone Stack Up? A Quick Comparison

| Attribute | Primidone | Phenobarbital | Valproic Acid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary mechanism | GABA enhancement + Na⁺ channel block (via phenobarbital metabolite) | GABA‑A potentiation | Multiple: Na⁺ channel block, increase GABA, inhibit T‑type Ca²⁺ channels |

| Half‑life | 5‑10 h (parent) / 70‑140 h (metabolite) | 80‑150 h | 9‑16 h |

| Common side‑effects | Drowsiness, ataxia, cognitive slowing | Weight gain, sedation, gingival hyperplasia | Hepatotoxicity, teratogenicity, tremor |

| Drug‑interaction risk | High - CYP inducer/ inhibitor | Moderate - enzyme inducer | Moderate - protein binding displacement |

| Pregnancy category | Category D (risk) | Category D | Category D |

The table shows why Primidone remains a solid middle‑ground: it offers the long‑acting stability of phenobarbital without some of the harsher sedation, yet it lacks the broad‑spectrum coverage of valproic acid.

Safety Profile: What to Watch For

Because the drug sits on the barbiturate family tree, side‑effects revolve around central‑nervous‑system depression:

- Daytime drowsiness - most common during titration.

- Ataxia and impaired coordination - can affect driving.

- Cognitive slowing - patients often report “brain fog”.

- Hematologic changes - rare leukopenia or thrombocytopenia.

Long‑term use raises a modest risk of osteopenia, especially in older adults, so bone‑density monitoring is advisable after five years of continuous therapy.

One key interaction worth noting: Primidone induces hepatic enzymes, potentially lowering the plasma levels of warfarin, oral contraceptives, and some antiretrovirals. Regular INR checks and contraceptive counseling become part of routine care.

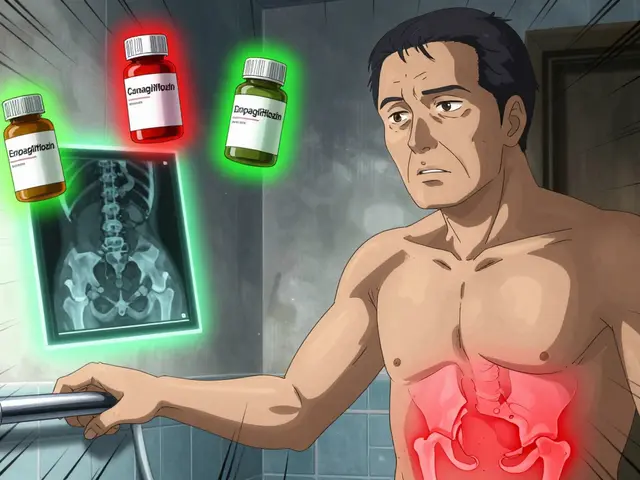

Dosing and Therapeutic Monitoring

Standard adult initiation starts at 25‑50 mg daily, split into two doses, then upward titrated by 25‑50 mg every 5‑7 days. Target maintenance ranges from 250‑1000 mg/day, depending on seizure type and tolerability.

Because phenobarbital carries most of the anti‑seizure weight, clinicians often measure total phenobarbital concentration. Therapeutic window sits between 10‑20 µg/mL; values above 30 µg/mL usually herald excessive sedation.

Emerging Research: Genetics and Precision Medicine

Recent genome‑wide association studies (GWAS) point to polymorphisms in the CYP2C19 gene influencing phenobarbital formation. Patients with the loss‑of‑function *2 allele may experience reduced conversion, leading to sub‑therapeutic seizure control. Some centres now recommend genotype‑guided dosing to avoid trial‑and‑error.

Another frontier is the exploration of Primidone’s off‑label neuroprotective potential. Small animal models suggest it may dampen excitotoxic injury after status epilepticus, but human data remain preliminary.

Bottom Line: When to Choose Primidone

If you need a once‑or‑twice‑daily regimen, especially for generalized tonic‑clonic seizures, and you can manage the slower onset, Primidone is a cost‑effective, well‑studied option. It works best when:

- The patient tolerates mild sedation.

- There’s no need for rapid seizure control (e.g., breakthrough clusters).

- Drug‑interaction vigilance is feasible.

In refractory cases or when rapid titration is crucial, newer agents like levetiracetam or lacosamide may take precedence.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take for Primidone to start working?

Most patients notice a reduction in seizure frequency after 1‑2 weeks of steady dosing, but the full effect may require 4‑6 weeks as phenobarbital levels build up.

Can Primidone be used during pregnancy?

Primidone is classified as Category D, meaning there is evidence of risk to the fetus. It should be reserved for cases where no safer alternative exists, and the benefits outweigh the potential harm.

What are the signs of an overdose?

Severe drowsiness, confusion, shallow breathing, and loss of coordination are warning signs. Immediate medical attention is required.

Does Primidone interact with alcohol?

Yes. Alcohol amplifies CNS depression, increasing sedation and the risk of respiratory depression. Patients should avoid or limit alcohol while on therapy.

How is Primidone different from Phenobarbital?

Primidone is a pro‑drug that converts to phenobarbital in the liver, offering a smoother titration curve and slightly fewer sedative side‑effects. Phenobarbital, on the other hand, works directly and has a longer half‑life, making it useful for patients needing very stable levels.

Understanding the science behind Primidone helps clinicians fine‑tune therapy and empowers patients to ask the right questions. Whether you’re starting a new regimen or evaluating long‑term control, the dual GABA‑enhancing and sodium‑channel‑blocking actions, together with its unique metabolism, make Primidone a cornerstone in the anti‑seizure toolbox.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published.

9 Comments

Primidone has been a workhorse in epilepsy treatment for many decades. It works by boosting GABA activity while also dampening sodium channel firing. The drug itself is a pro‑drug that turns into phenobarbital in the liver. This conversion takes a few hours and provides the bulk of the anti‑seizure effect. Because of that, the therapeutic levels take longer to appear than with newer agents. Usually patients start seeing fewer seizures after one to two weeks of steady dosing. Full control may need four to six weeks as phenobarbital builds up. The slow titration helps reduce side‑effects such as drowsiness and ataxia. Most clinicians begin with 25‑50 mg per day and increase by 25‑50 mg every week. The goal is to reach a maintenance dose between 250 and 1000 mg daily. Blood levels of phenobarbital are often monitored rather than primidone itself. The therapeutic window for phenobarbital is roughly 10‑20 µg/mL. Levels above 30 µg/mL often cause excessive sedation. Patients should be aware that alcohol can magnify CNS depression. Drug interactions are common because primidone induces hepatic enzymes. Strong CYP2C19 inhibitors can lower the conversion to phenobarbital and reduce efficacy. Overall, primidone remains a cost‑effective option for generalized tonic‑clonic and myoclonic seizures when patients can tolerate a gradual onset of action.

I appreciate the thorough walk‑through. It's useful to know the titration schedule in detail. The gradual rise really does help keep side‑effects manageable.

Pharmacodynamically, primidone acts as a GABA‑ergic modulator and sodium‑channel blocker via its metabolite phenobarbital. Its half‑life variability necessitates careful therapeutic drug monitoring.

While the exposition is comprehensive, one must not overlook the ethical considerations of prescribing a Category D drug during pregnancy. The risk‑benefit analysis should be scrupulously applied. Moreover, the reliance on phenobarbital metabolism may pose challenges in polypharmacy scenarios.

One could reflect on how the slow onset of primidone mirrors the patient’s journey toward stability. Patience becomes a therapeutic ally.

Great summary, and, as a mentor, I’d add that monitoring bone density after long‑term use is prudent; also, keep an eye on INR if the patient is on warfarin, because enzyme induction can lower anticoagulant levels.

This is helpful.

Thanks for the clear explanation, it’s reassuring to see such detailed guidance. I’ll share this with the community.

Remember, patient education is key; ensure they understand the gradual effect and the importance of adherence, especially when titrating doses.