Hypoglycemia Risk Assessment Tool

Personalized Hypoglycemia Risk Assessment

This tool evaluates key factors that increase hypoglycemia risk in older adults with diabetes. Based on your inputs, we'll provide tailored recommendations to improve safety.

Your Risk Factors

When blood sugar drops below 70 mg/dL, it’s called hypoglycemia. For most people, that means sweating, shakiness, or a racing heart. But for older adults with diabetes, it often looks completely different - confusion, dizziness, or even a sudden silence. By the time family members notice something’s wrong, the person may already be in danger. Hypoglycemia isn’t just uncomfortable for seniors; it’s a silent threat that increases the risk of falls, fractures, heart attacks, and even death. And yet, it’s still overlooked, underreported, and poorly managed in this population.

Why Older Adults Are at Higher Risk

The body’s ability to protect itself from low blood sugar weakens with age. Older adults produce less epinephrine and glucagon - the hormones that normally kick in to raise blood sugar when it drops. Studies show this response is cut by 30% to 50% compared to younger people. That means when blood sugar starts falling, the body doesn’t sound the alarm until it’s dangerously low - often below 50 mg/dL. By then, the brain is already starved of glucose, leading to confusion, slurred speech, or loss of consciousness. Add to that the fact that many older adults live with multiple chronic conditions - kidney disease, heart failure, dementia - and take five or more medications. Each one adds risk. For example, those with chronic kidney disease (eGFR under 60 mL/min) are 2.7 times more likely to have a severe hypoglycemic episode. And drugs like glyburide, a long-acting sulfonylurea, are linked to a 50% higher risk of dangerous lows compared to safer alternatives like glipizide. The American Geriatrics Society explicitly lists glyburide as a medication to avoid in older adults.The Hidden Symptoms

Classic signs of low blood sugar - trembling, sweating, hunger - are often absent in seniors. Instead, hypoglycemia shows up as behavioral changes. A normally alert grandmother might suddenly not recognize her own children. A grandfather might sit quietly, staring into space, or wander around confused. These aren’t signs of dementia; they’re signs of low glucose. In fact, 40% to 60% of hypoglycemic episodes in older adults go unreported because neither the person nor their caregiver recognizes them as such. This is especially dangerous for those with cognitive decline. If someone can’t remember how to test their blood sugar, or doesn’t understand why they need to eat juice when they feel off, they can’t treat themselves. Caregivers report cases where a senior’s blood sugar dropped below 40 mg/dL before anyone realized something was wrong. By then, emergency glucagon was needed - not juice or glucose tablets.The Real Consequences

Hypoglycemia doesn’t just cause immediate distress. It has lasting effects. Each episode increases the risk of falling by 40% and the risk of hip fracture by 25%. One study followed 782 older adults with diabetes for five years. Those who had even one severe hypoglycemic event were 2.5 times more likely to die during that time. Even after adjusting for other health problems, the risk stayed elevated - 1.4 times higher. Worse, repeated lows can damage the brain. Over two years, seniors who had frequent hypoglycemia were 1.8 times more likely to develop new cognitive impairment. It’s not just about memory - it’s about independence. A single fall can lead to surgery, hospitalization, and loss of mobility. A single episode of confusion can lead to a nursing home placement. And the costs add up. Each severe hypoglycemia event costs an average of $1,200 in emergency care. In the U.S., hypoglycemia sends about 100,000 older adults to the emergency room every year. For a population where 25% of adults over 65 have diabetes, this isn’t a rare problem - it’s a systemic one.

Medication Risks and Safer Choices

Not all diabetes medications are equal when it comes to hypoglycemia risk. Sulfonylureas (like glyburide, glipizide, glimepiride) and insulin are the biggest culprits. Glyburide, in particular, stays in the body too long and builds up in older adults with slower metabolism or kidney issues. That’s why experts recommend switching to glipizide or glimepiride - shorter-acting and less likely to cause lows. Insulin regimens also need to be reevaluated. Many seniors are on rigid, high-dose insulin plans designed for younger, healthier patients. But tight control isn’t worth the risk. The American Diabetes Association now recommends individualized A1c goals: under 7.0% for healthy seniors, but up to 8.5% for those with multiple illnesses, limited life expectancy, or cognitive issues. A1c isn’t the goal - safety is. Newer medications like GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors carry little to no hypoglycemia risk on their own. When used with insulin or sulfonylureas, they can actually reduce the need for those riskier drugs. In one real-world case, reducing insulin from 40 units to 20 units per day prevented weekly lows while keeping A1c at a safe 7.8%.Prevention Plans That Work

A good prevention plan isn’t just about drugs. It’s a full system. The American Diabetes Association recommends four key steps:- Assess risk - Ask: Has the person had a low in the past year? Are they on insulin or sulfonylureas? Do they have kidney disease, dementia, or live alone?

- Review medications - Eliminate high-risk drugs like glyburide. Simplify regimens. Consider switching to safer alternatives.

- Set realistic goals - Forget “normal” blood sugar targets. Aim for time-in-range: 50% of the day between 70 and 180 mg/dL, with less than 1% below 54 mg/dL.

- Teach action steps - Everyone - patient and caregiver - needs to know how to recognize a low, treat it, and use glucagon.

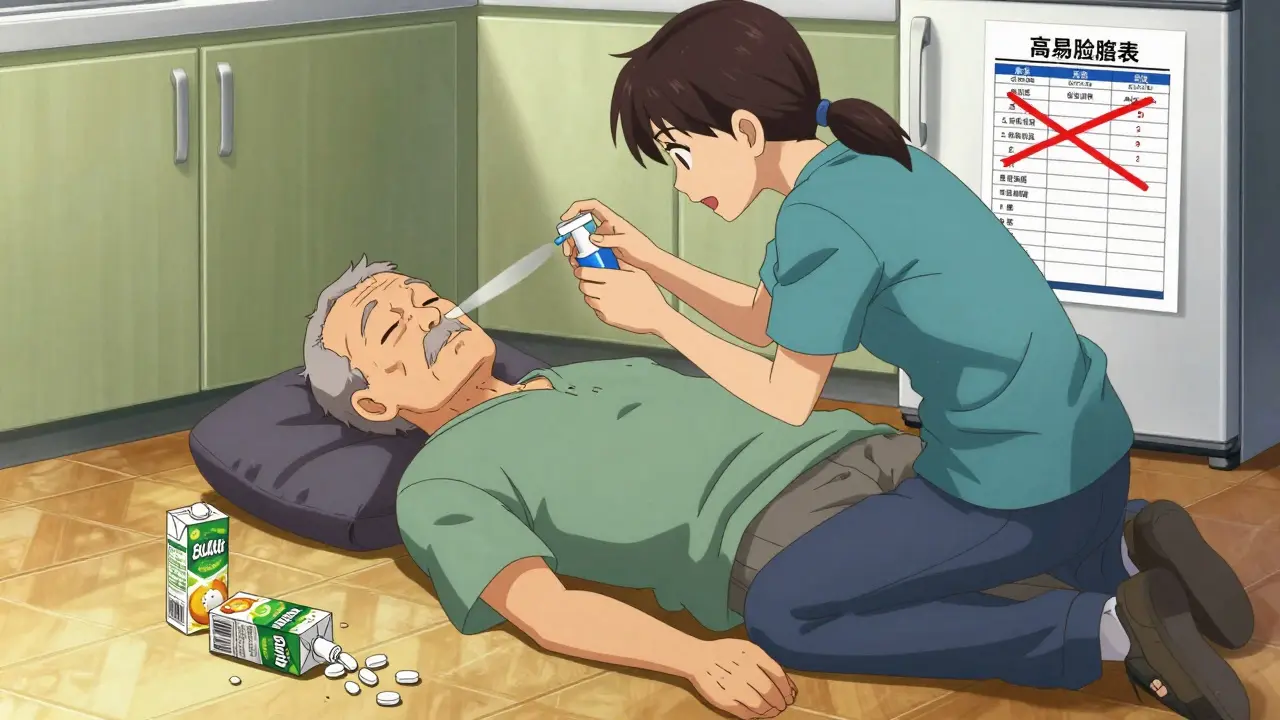

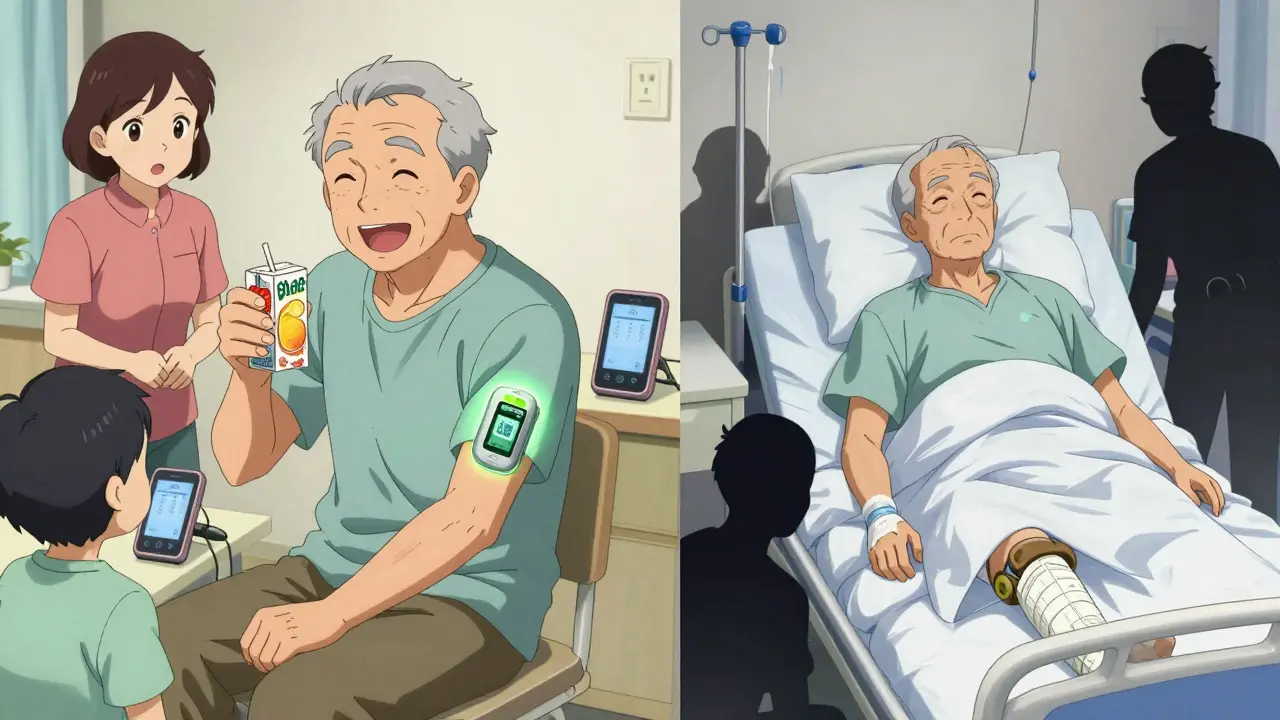

Technology That Saves Lives

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are the most effective tool for preventing lows in older adults. Devices like the Dexcom G7 or Abbott FreeStyle Libre 3 give real-time alerts when blood sugar is dropping - even if the person doesn’t feel it. Studies show CGM use cuts hypoglycemia by 40%. Yet only 15% of older adults use them. Why? Cost. Medicare only covers CGMs for people on insulin, leaving out many seniors on sulfonylureas who are just as vulnerable. Providers often don’t know how to prescribe them. And some families think the device is too complicated. But the reality is simpler: a CGM that beeps when blood sugar hits 65 mg/dL can prevent a fall, a hospital trip, or worse. Nasal glucagon (like Baqsimi) is another breakthrough. Older adults often can’t swallow pills or juice during a low. Nasal glucagon works without injection or swallowing - just spray it in the nose. One caregiver said it saved her mother’s life when she couldn’t swallow anything.What Families and Caregivers Can Do

You don’t need to be a doctor to help. Here’s what works:- Keep fast-acting sugar - glucose tabs, juice boxes, or honey - in every room, purse, and car.

- Teach everyone in the household how to use glucagon. Practice with the trainer kit.

- Set phone alarms to check blood sugar at meals and bedtime.

- Watch for subtle signs: confusion, slurring words, unusual quietness, or not recognizing familiar people.

- Ask the doctor: “Is my loved one on a medication that could cause dangerous lows?”

Final Thought: Safety Over Numbers

For too long, the goal in diabetes care has been to get A1c as low as possible. But for older adults, that mindset can be deadly. A1c of 7.5% with no lows is far better than an A1c of 6.8% with three emergency visits. The goal isn’t perfection - it’s protection. Reduce the risk of falling. Prevent brain damage. Avoid the hospital. Keep independence. The science is clear. The tools exist. What’s missing is the will to change. It’s time to stop treating hypoglycemia as an afterthought - and start treating it as the emergency it is.What are the most dangerous diabetes medications for older adults?

Long-acting sulfonylureas like glyburide are the most dangerous. They stay in the body too long, especially in seniors with kidney issues, and cause severe, unpredictable lows. The American Geriatrics Society advises avoiding glyburide entirely. Safer alternatives include glipizide, glimepiride, or non-sulfonylurea options like GLP-1 agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors.

Can older adults use continuous glucose monitors (CGMs)?

Yes - and they should. CGMs are especially helpful for older adults because they alert users to drops before symptoms appear. Medicare currently only covers CGMs for people on insulin, which leaves many at-risk seniors uncovered. But if a doctor prescribes one for safety reasons, many insurers will approve it. Devices like the FreeStyle Libre 3 are easy to use and don’t require fingersticks.

What should I do if my elderly parent has a low blood sugar episode?

If they’re awake and able to swallow, give 15 grams of fast-acting sugar - 4 ounces of juice, 3-4 glucose tablets, or a tablespoon of honey. Wait 15 minutes and recheck blood sugar. If they’re confused, unconscious, or can’t swallow, use nasal glucagon (like Baqsimi) immediately. Call 911 if there’s no improvement after glucagon. Never try to give food or drink to someone who is unconscious.

Is it safe to reduce diabetes medication in older adults?

Yes - and often necessary. Many older adults are on medication doses meant for younger, healthier patients. Reducing insulin or switching from glyburide to a safer drug can dramatically lower hypoglycemia risk without worsening overall control. In one study, 20% of patients were able to stop insulin or sulfonylureas entirely after a structured review. Always work with a doctor - never adjust doses on your own.

How can I tell if my elderly relative is having a low blood sugar episode?

Forget sweating or shaking. In older adults, watch for sudden confusion, slurred speech, unusual quietness, staring blankly, or not recognizing family members. They may seem “off” or like they’re in a daze. These are signs of neuroglycopenia - the brain is starved of glucose. Test blood sugar immediately if you see these signs, even if they say they feel fine.