Every year, thousands of workers develop lung diseases that don’t come from smoking or pollution-they come from their jobs. Silicosis and asbestosis aren’t rare anomalies. They’re preventable tragedies that still happen because safety measures are ignored, skipped, or poorly enforced. These aren’t diseases of the past. They’re happening right now, in construction sites, mines, factories, and demolition crews across the country.

What Silicosis and Asbestosis Actually Do to Your Lungs

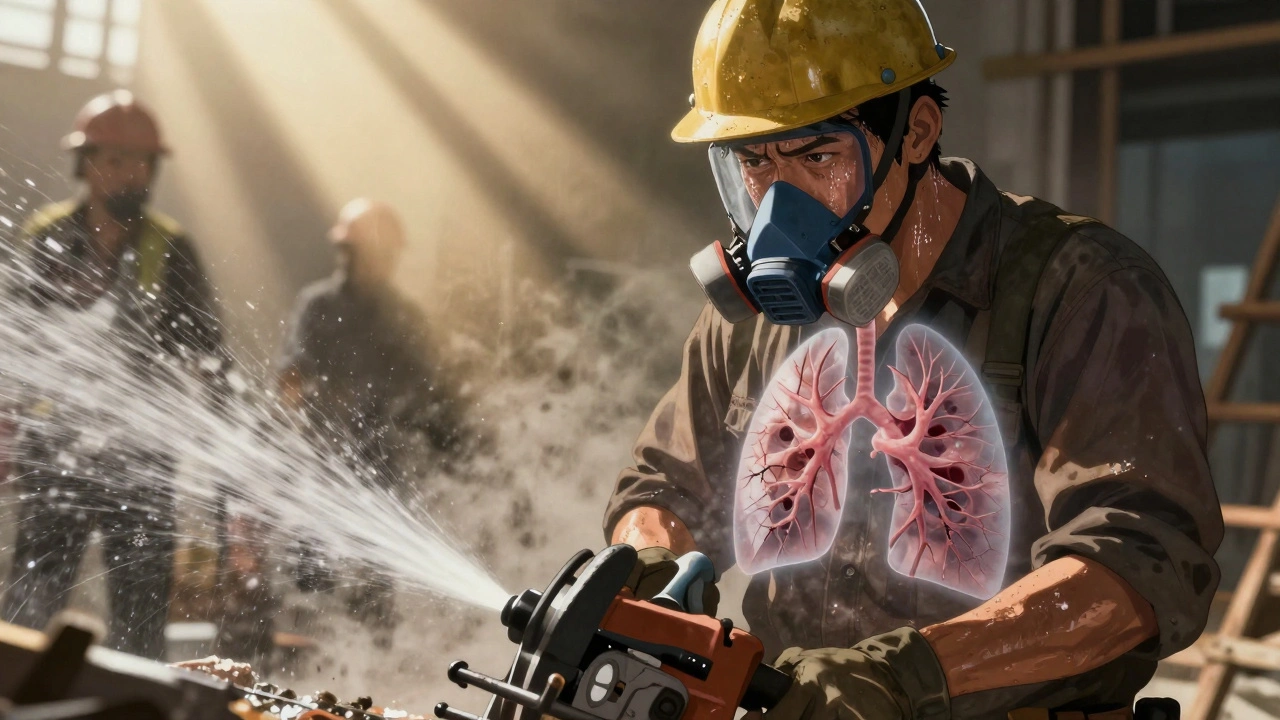

Silicosis starts when you breathe in tiny particles of crystalline silica-found in sand, stone, concrete, and mortar. These particles don’t just disappear. They get stuck in your lungs, and your body tries to fight them off by creating scar tissue. Over time, that scar tissue builds up, stiffens your lungs, and makes it harder to breathe. You won’t feel it at first. No cough, no chest pain. But after 10, 15, even 20 years of exposure, you’ll start gasping for air. By then, it’s too late. The damage is permanent.

Asbestosis works the same way-but with asbestos fibers. These microscopic threads come from old insulation, pipe wrap, ceiling tiles, and brake linings. When disturbed, they float in the air and get inhaled. Your lungs can’t break them down. Instead, they wrap them in scar tissue, slowly suffocating you from the inside. Unlike some diseases, there’s no safe level of asbestos exposure. Even a single fiber can, over decades, lead to fatal scarring.

These aren’t just medical conditions. They’re death sentences with long waiting periods. Between 2004 and 2014, more than 1,100 U.S. workers died from asbestosis. Silicosis kills about 1,200 people each year in the U.S. alone. And most of them worked in jobs where the risk was known, avoidable, and preventable.

Why These Diseases Keep Happening

You’d think after 150 years of documented cases, we’d have this figured out. But we haven’t. Why? Because prevention isn’t about technology-it’s about culture.

On construction sites, dry cutting of stone or concrete is faster. It’s cheaper. Workers are told to “just get it done.” Wet cutting, which cuts silica dust by 90%, slows things down. Local exhaust ventilation systems cost $2,000-$5,000 per tool. Many small shops don’t have the budget-or the will-to install them.

Then there’s PPE. N-95 masks are common. But they only filter 95% of particles 0.3 microns in size. For silica and asbestos, you need P-100 respirators, which filter 99.97%. Yet a CDC report found that 68% of workers who complain about respiratory protection say the masks are uncomfortable, hot, or don’t fit right. So they loosen straps. They wear them only when OSHA inspectors are around. Some even cut holes in them to breathe easier.

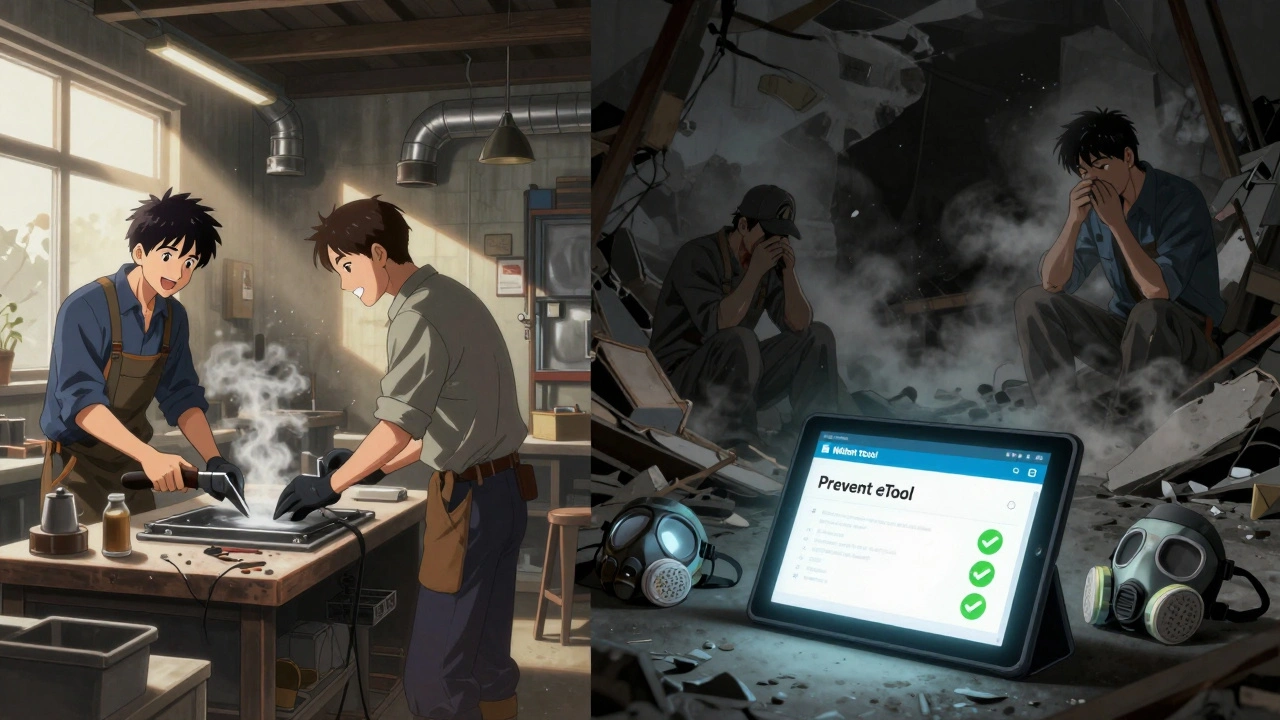

And it’s not just workers. Supervisors often don’t wear PPE themselves. If the boss doesn’t wear a respirator, why should you? A study of 15 construction companies showed that when managers modeled proper PPE use 100% of the time, respiratory incidents dropped by 65% over three years.

The Hierarchy of Prevention: What Actually Works

There’s a clear order of effectiveness when it comes to stopping these diseases. It’s not a suggestion-it’s science.

- Elimination: Don’t use silica or asbestos at all. Replace concrete with alternative materials where possible.

- Substitution: Use low-silica sand or engineered stone that meets safety standards.

- Engineering Controls: This is where you get the biggest win. Wet cutting, local exhaust ventilation, and sealed enclosures reduce exposure by 70-90%. These aren’t optional. They’re the backbone of real protection.

- Administrative Controls: Limit how long workers are exposed. Rotate tasks. Schedule high-dust work for low-occupancy times.

- PPE: The last line of defense. Only effective if worn correctly, fit-tested annually, and maintained properly.

Here’s the hard truth: relying on masks alone is like using a bucket to bail out a sinking boat. Engineering controls are the pump. They stop the water at the source.

What You Need to Do: A Practical Prevention Plan

If you’re a worker, a supervisor, or a business owner, here’s exactly what you need to do-right now.

- Use wet methods for cutting, grinding, or drilling stone, concrete, or tile. Water suppresses dust at the source. It’s simple. It’s cheap. It works.

- Install local exhaust ventilation on every tool that creates dust. Even a small vacuum attachment on a grinder can cut exposure by 80%.

- Use P-100 respirators for any job with silica or asbestos risk. N-95s are not enough. And they must be fit-tested every year. No exceptions.

- Train properly. OSHA requires 2 hours of training. The American Lung Association recommends 4-6 hours. Don’t cut corners. Workers need to understand why this matters-not just how to put on a mask.

- Get spirometry tested. Baseline lung function test when you start the job. Then every 5 years. If you’re at high risk, get it every year. Early detection means you can stop exposure before it’s too late.

- Keep respirators clean. Store them in sealed containers. Don’t leave them on dirty floors or in hot trucks. A dirty mask is a useless mask.

- Speak up. If you see unsafe practices, report them. OSHA’s whistleblower protections exist for a reason. No one should lose their job for protecting their lungs.

Who’s Falling Through the Cracks

Small businesses are the weakest link. In Wisconsin, 78% of companies with fewer than 20 employees had no formal respiratory protection program. These are the shops that can’t afford consultants, don’t have safety officers, and rely on word-of-mouth advice. They’re not negligent-they’re overwhelmed.

And then there’s the aging workforce. One in four construction workers is over 55. Many have asthma, COPD, or past smoking histories. They’re more vulnerable. Their lungs can’t handle extra stress. Yet they’re often the ones doing the riskiest jobs-demolition, pipe removal, tile cutting-because they’ve been doing it for decades.

There’s also the hidden danger: renovation. People don’t realize that tearing down an old house built before 1980 could release asbestos. Sanding old floors might release silica from old paint or joint compound. Homeowners and DIYers are at risk too.

What’s Changing-And What’s Not

There’s progress. OSHA’s 2016 Silica Standard was a game-changer. It’s expected to prevent 1,600 new cases of silicosis each year and save 900 lives. In 2023, OSHA launched a National Emphasis Program on silica. They’ve done over 1,200 inspections and issued nearly 1,000 citations. Fines are climbing.

NIOSH’s new “Prevent eTool” digital platform gives workers and employers step-by-step guides for 15 high-risk industries. Companies using it saw a 40% drop in respiratory incidents in just six months.

But enforcement is uneven. In 2021, OSHA cited over 1,000 construction companies for silica violations-totaling $3.2 million in fines. That sounds like a lot. But for a big contractor, it’s just a line item in the budget. For a small shop, it could shut them down.

And while Europe is moving toward eliminating all occupational lung diseases by 2030, the U.S. still treats prevention as a checklist, not a mission.

The Bottom Line

Silicosis and asbestosis are not accidents. They’re failures. Failures of leadership. Failures of training. Failures of will.

You don’t need a fancy machine or a huge budget to prevent them. You need to care enough to do the basics right: wet cutting, proper masks, fit testing, and training that sticks. You need to treat worker health like a core business value-not an afterthought.

Every worker deserves to go home at the end of the day with lungs that still work. That’s not a luxury. It’s a right.

Can you get silicosis from one exposure?

No, silicosis doesn’t happen from a single day of exposure. It develops over years-usually 10 to 30-of repeated inhalation of silica dust. But there’s a rare and aggressive form called acute silicosis that can develop after just a few months of very high exposure, like in sandblasting without protection. Even then, it’s not one event-it’s constant, heavy exposure over time.

Is asbestosis the same as mesothelioma?

No. Asbestosis is scarring of the lung tissue from asbestos fibers. It’s a non-cancerous but progressive disease that makes breathing harder. Mesothelioma is a deadly cancer of the lining of the lungs, heart, or abdomen, caused by asbestos exposure. Both come from asbestos, but they’re different diseases with different outcomes. One is chronic and debilitating; the other is fatal and aggressive.

Do N-95 masks protect against silica and asbestos?

N-95 masks filter 95% of particles 0.3 microns in size, which is good for many dusts. But silica and asbestos fibers are often smaller and more dangerous. P-100 respirators filter 99.97% of those particles and are the minimum standard for these hazards. N-95s are not enough for long-term or high-exposure work. OSHA requires P-100 for known asbestos or silica risks.

Can you test your lungs for early signs of silicosis or asbestosis?

Yes. Spirometry is a simple breathing test that measures lung function. Chest X-rays and CT scans can show scarring. But the key is timing: get tested before you’re exposed, then every 5 years. If you’re at high risk, get tested annually. Early detection doesn’t reverse damage-but it stops it from getting worse. Many workers don’t realize they’re at risk until they’re already struggling to breathe.

Is it legal to work with asbestos today?

It’s not banned in the U.S., but it’s heavily regulated. You can’t use asbestos in new products, but it’s still in older buildings-pipes, insulation, tiles, roofing. If you’re removing or disturbing it, you must follow strict OSHA and EPA rules: wet methods, sealed containment, trained workers, proper disposal. Unlicensed removal is illegal and extremely dangerous.

What if my employer won’t give me proper protection?

You have rights. OSHA requires employers to provide appropriate PPE, training, and exposure controls. If they don’t, you can file a confidential complaint with OSHA. You can’t be fired or punished for reporting unsafe conditions. Whistleblower protections are real. Your health is worth more than your job. Don’t wait until you’re sick to act.

Can smoking make silicosis or asbestosis worse?

Yes. Smoking increases your risk of developing these diseases by 50-70%. It also speeds up lung damage and makes symptoms worse. If you’re exposed to silica or asbestos, quitting smoking is one of the most important things you can do to protect your lungs-even if you’ve been smoking for years.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published.

9 Comments

Honestly, this hit me hard. I grew up watching my uncle work in demolition-he never wore anything but an N-95, and now he’s on oxygen at 58. No one told him it wasn’t enough. We treat these jobs like they’re just ‘dirty work,’ but they’re life-shortening. Why does it take someone dying before we actually act?

So let me get this straight-we spend billions on fancy safety apps and VR training, but the solution is… water and a mask? Mind blown.

Let’s be brutally honest: this isn’t about PPE or wet cutting-it’s about the systemic devaluation of blue-collar labor. You don’t need a CDC report to know silica kills. You need to acknowledge that capitalism prioritizes profit over person. The 68% of workers who skip respirators aren’t negligent-they’re responding to a culture that tells them their lungs are expendable. This isn’t an occupational hazard. It’s a class issue wrapped in a dust cloud.

Oh my god, I’ve been reading this while sipping my oat milk latte, and I just had a full existential crisis. The hierarchy of prevention? It’s literally the pyramid of human dignity. Elimination > substitution > engineering controls > administrative > PPE. And yet, we treat PPE like it’s the holy grail. It’s not. It’s the Band-Aid on a severed artery. The fact that we still debate N-95s vs. P-100s in 2025 is a national disgrace. We’ve got drones that can deliver pizza, but we can’t engineer a dust-free concrete cut? We’re failing on a philosophical level.

And don’t get me started on the ‘boss doesn’t wear it so I won’t either’ mentality. That’s not culture-it’s cowardice dressed up as conformity. Leadership isn’t a title. It’s a behavioral contract. If your manager won’t wear the mask, they’re not leading-they’re complicit.

The real tragedy? The workers who’ve been doing this for 30 years. They’re the ones who know the rhythm of the job, the sound of the tool, the way the dust settles. But they’re also the ones who’ve been told ‘you’re fine, you’ve survived this long.’ Survivorship bias is a silent killer. And now, their lungs are the graveyard of bad policy.

And DIYers? Please. If you’re sanding old floors in your 1972 ranch house, you’re not ‘renovating’-you’re performing a slow-motion suicide with a orbital sander. You need a P-100. Not because I said so. Because science said so. And science doesn’t care how cute your Pinterest board is.

OSHA’s citations? $3.2 million sounds like a lot until you realize it’s less than the cost of one luxury SUV for a Fortune 500 contractor. We’re punishing the symptom, not the disease. We need to criminalize negligence. Not fines. Criminal charges. Jail time. If you knowingly expose someone to a known carcinogen for the sake of speed, you’re not a contractor-you’re a poisoner.

And smoking? Oh, honey. Smoking while exposed to silica is like pouring gasoline on a campfire and then asking why it’s so hot. The synergy is monstrous. Quitting isn’t ‘good advice’-it’s a survival imperative. And if you think you can ‘quit later,’ you’re already dead. Your lungs just haven’t caught up yet.

There’s a reason Europe is aiming for zero by 2030. They stopped treating this like a compliance checklist. They treated it like a moral imperative. We’re still stuck in the 1980s, arguing about whether wet cutting slows down the job. It doesn’t slow down the job. It slows down the funeral.

my uncle died of asbestosis in 2019 and no one ever told him the tiles in the school he worked at had asbestos… i just keep thinking if someone had just said ‘hey, don’t scrape that’… maybe he’d still be here. i dont even know how to feel about it anymore.

Thank you for this comprehensive and meticulously researched exposition. I would like to respectfully add that, in the Indian context, informal sector laborers-particularly in stone-cutting and brick-making-are often unaware of even the most basic protective measures. Many lack access to clean water for wet methods, let alone P-100 respirators. Structural interventions, such as government-subsidized dust-extraction units for small workshops, are urgently needed. Moreover, community-based health education, delivered in local languages by trained peer educators, has shown measurable success in pilot programs in Rajasthan and Gujarat. Prevention is not merely a technical problem-it is a social one.

...so... you're telling me the government knew this for decades... and still let it happen? ...and now they want us to trust OSHA? ...and you really believe that 'Prevent eTool' is going to fix this? ...they're just putting a pretty sticker on a corpse. ...they don't want to stop it... they just want to make it look like they're trying... so they can sleep at night... while the workers cough themselves to death... and no one's going to do anything... because it's easier to ignore...

While I appreciate the earnestness of the piece, one must question the epistemological foundation of its prescriptive framework. The hierarchy of controls, though pedagogically convenient, is predicated upon an assumption of universal compliance and institutional integrity-both of which are empirically untenable in a neoliberal labor ecosystem. The suggestion that ‘wet cutting’ is ‘cheap’ ignores the externalized costs of water infrastructure, wastewater management, and labor reallocation. Furthermore, the invocation of ‘fit-testing’ as a panacea neglects the phenomenological reality of worker discomfort, which is itself a form of epistemic violence. One cannot legislate bodily autonomy through respirators. The real failure is not in the absence of engineering controls-but in the absence of a moral economy that values human life over productivity metrics.

my dad worked in a tile shop for 25 years. he never complained. last year he got a CT scan. the doc said ‘your lungs look like they’ve been through a sandstorm.’ he just nodded and said ‘well, i did my job.’ i cried in the parking lot. no one ever told him he could’ve lived longer.