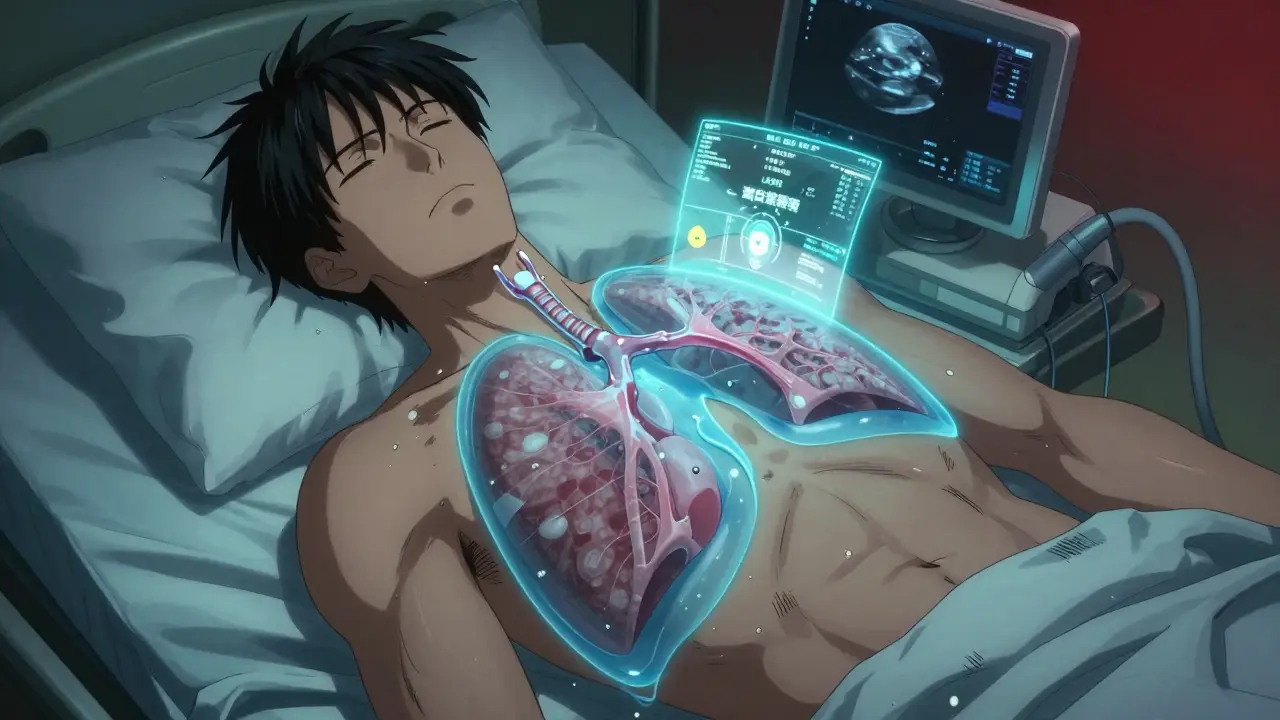

When your lungs can’t expand fully because fluid is squeezing them, breathing becomes a struggle. That’s pleural effusion-a buildup of fluid between the layers of tissue surrounding your lungs. It’s not a disease itself, but a sign something else is wrong. About 1.5 million people in the U.S. get this each year, and for many, it’s linked to heart failure, pneumonia, or cancer. The good news? We know how to find out why it’s happening, how to remove the fluid safely, and how to stop it from coming back.

What Causes Pleural Effusion?

Pleural effusions fall into two main types: transudative and exudative. The difference matters because it tells you what’s really going on inside your body.Transudative effusions happen when fluid leaks out because of pressure changes or low protein levels. The most common cause? Congestive heart failure. In fact, nearly 90% of transudative cases come from this. When the heart can’t pump well, pressure builds up in the blood vessels, pushing fluid into the pleural space. Liver cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome (where your kidneys leak protein) are other causes, but they’re much rarer.

Exudative effusions are more serious. They happen when inflammation, infection, or cancer damages the tiny blood vessels in the pleura, letting fluid, proteins, and cells leak out. Pneumonia is the top culprit-responsible for 40 to 50% of exudative cases. Cancer comes next, causing 25 to 30%. That includes lung cancer, breast cancer, or lymphoma spreading to the lining of the lungs. Pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in the lung) and tuberculosis are less common but still important to check for.

Light’s criteria, developed in 1972, is the gold standard for telling these two apart. If your pleural fluid has a protein-to-blood protein ratio over 0.5, an LDH ratio over 0.6, or LDH levels higher than two-thirds of the normal blood range, it’s exudative. This test is 99.5% accurate. Missing it means you might overlook cancer or an infection that needs urgent treatment.

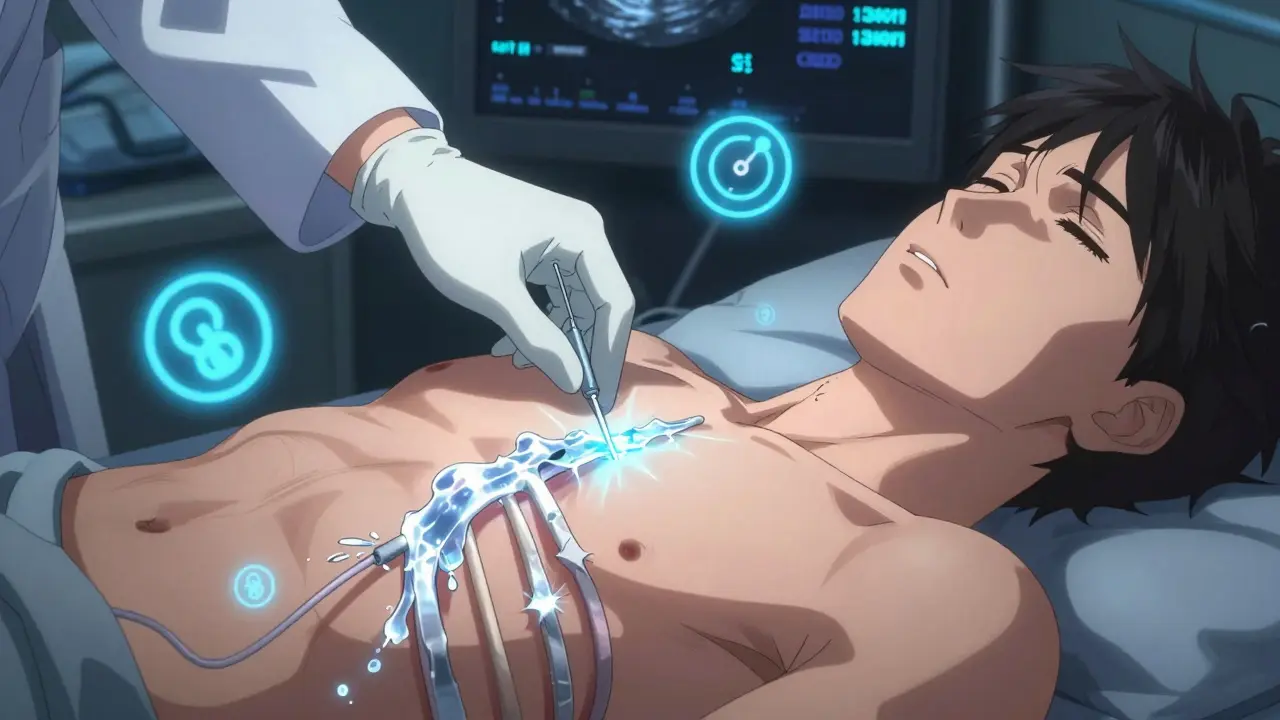

When and How Is Thoracentesis Done?

If you’re short of breath and an X-ray or ultrasound shows fluid around your lungs, your doctor will likely recommend thoracentesis. This is a simple procedure to remove fluid-both to help you breathe better and to test what’s causing the problem.Ultrasound guidance is now required. Before ultrasound, about 19% of patients had complications like a collapsed lung. Now, with real-time imaging, that number drops to just 4%. The procedure is usually done between the 5th and 7th ribs on your side, near the armpit. A thin needle or catheter goes in, and fluid is drawn out. For diagnosis, they take 50 to 100 milliliters. For relief, they can safely remove up to 1,500 milliliters in one go.

The fluid gets tested for:

- Protein and LDH (to classify as transudate or exudate)

- Cell count (to spot infection or cancer cells)

- pH (below 7.2 means complicated pneumonia or empyema)

- Glucose (low levels suggest infection or rheumatoid arthritis)

- Cytology (to find cancer cells-successful in 60% of malignant cases)

- Amylase (high levels point to pancreatitis)

- Hematocrit (if pleural fluid is more than 1%, it could mean a pulmonary embolism or pneumonia)

Complications are rare with ultrasound, but they can happen. Pneumothorax (collapsed lung) occurs in 6 to 30% of unguided procedures, but only 1 to 2% with ultrasound. Re-expansion pulmonary edema-fluid flooding the lung after it’s been compressed too long-is rare but dangerous. It’s more likely if you remove more than 1.5 liters at once. That’s why doctors now use pleural manometry: measuring pressure during drainage. If pressure stays below 15 cm H₂O, the risk of this complication drops to less than 5%.

How to Prevent Pleural Effusion from Coming Back

Removing fluid once doesn’t fix the root problem. That’s why recurrence is common-especially with cancer.For malignant effusions: If cancer caused the fluid, there’s a 50% chance it’ll come back within 30 days after just draining it. That’s why doctors move quickly to prevent it. The two main options are pleurodesis and indwelling pleural catheters.

Pleurodesis means sticking the lung lining to the chest wall so no space is left for fluid. Talc is the most effective agent, working in 70 to 90% of cases. But it’s painful-up to 80% of patients report moderate to severe pain after. Hospital stays average 7 days.

Indwelling pleural catheters are now the preferred choice for many. These are small tubes left in place for weeks. You or a caregiver can drain fluid at home, usually once a week. Success rates hit 85 to 90% at six months. Hospital stays drop from 7 to just 2 days. Patients report better quality of life. This is now the first-line recommendation for trapped lung from cancer, according to the European Respiratory Society.

For heart failure: The key is managing the heart. Diuretics (water pills) like furosemide help. But the real game-changer is using NT-pro-BNP blood tests to guide treatment. When doctors adjust meds based on these levels, recurrence drops from 40% to under 15% in three months. ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers also help the heart heal.

For pneumonia-related effusions: Antibiotics are essential. But if the fluid is thick, infected, or has a pH below 7.2 or glucose under 40 mg/dL, you need drainage. Otherwise, it turns into empyema-a pus-filled infection that may require surgery. About 30 to 40% of untreated cases progress to this stage.

After heart surgery: About 1 in 5 patients get fluid buildup. Most go away on their own. But if more than 500 mL drains per day for three days straight, doctors leave a chest tube in longer. With proper management, recurrence drops to just 5%.

What Doctors Are Doing Differently Now

Ten years ago, doctors drained fluid and hoped for the best. Now, everything is more targeted.One big change: no more routine pleurodesis for non-cancer effusions. The American Thoracic Society says there’s no proof it helps for heart failure or liver disease. It just adds risk and pain.

Another shift: testing more than just fluid. Biomarkers like pH, glucose, and LDH are now standard. A pH below 7.2 in a parapneumonic effusion means you’re looking at a surgical emergency.

And the biggest win? Survival. Five-year survival for people with malignant pleural effusion has jumped from 10% in 2010 to 25% today. Why? Better cancer treatments, earlier diagnosis, and smarter drainage options like indwelling catheters that let people live at home instead of in the hospital.

As Dr. Richard Light said back in 2018: "Treating the effusion without treating the cause is like bailing water from a sinking boat without patching the hole." That’s the core of modern care. Find the cause. Fix the cause. Then manage the fluid smartly.

What You Should Know

- If you have unexplained shortness of breath, get an ultrasound. Don’t wait for chest pain. - Don’t assume small effusions are harmless. 25% of undiagnosed cases turn out to be cancer. - Ultrasound-guided thoracentesis isn’t optional-it’s the standard. Ask if it’s being used. - For cancer-related fluid, ask about indwelling catheters. They’re less invasive and more effective than repeated draining. - Heart failure patients: monitor your weight daily. A sudden 2-kg gain can mean fluid is building up before you feel it. - Avoid unnecessary thoracentesis. A 2019 study found 30% of procedures on small, asymptomatic effusions provided zero benefit.Pleural effusion is common, but it’s not a death sentence. With the right diagnosis, the right procedure, and the right follow-up plan, most people get back to living-without constant hospital visits or breathing struggles.

What is the most common cause of pleural effusion?

The most common cause is congestive heart failure, responsible for about half of all pleural effusions. In transudative cases-which make up roughly 50% of total cases-heart failure accounts for 90%. Exudative effusions, which are often due to infection or cancer, are the second major group, with pneumonia being the top cause in that category.

Can pleural effusion be cured?

Pleural effusion itself isn’t a disease-it’s a symptom. So yes, it can be resolved if the underlying cause is treated. Heart failure-related effusions often resolve with diuretics and heart meds. Pneumonia-related effusions clear with antibiotics and drainage if needed. Cancer-related effusions can’t be "cured" in the traditional sense, but they can be controlled long-term with indwelling catheters or pleurodesis, allowing many patients to live at home with minimal symptoms.

Is thoracentesis painful?

The procedure is usually not painful. You’ll get a local anesthetic, so you’ll feel pressure but not sharp pain. Some people feel a brief ache when the fluid is being drained, especially if a lot is removed. Afterward, mild soreness at the needle site is common. With ultrasound guidance, complications like a collapsed lung are rare, which also reduces overall discomfort.

How long does it take to recover after thoracentesis?

Most people feel better immediately after the fluid is removed, especially if they were short of breath. You can usually go home the same day. Full recovery from the procedure itself takes a day or two. If you had a complication like a small pneumothorax, you might need to be monitored longer. For those with indwelling catheters, recovery is ongoing-you’ll manage drainage at home over weeks or months.

What are the risks of not treating a pleural effusion?

Untreated effusions can lead to serious problems. In pneumonia-related cases, fluid can turn into empyema-a dangerous pus infection requiring surgery. In cancer patients, fluid buildup can compress the lung further, making breathing impossible without intervention. Persistent fluid also increases the risk of scarring (fibrosis), which permanently limits lung function. And if the cause is heart failure or cancer, delaying treatment reduces survival chances significantly.

Can pleural effusion come back after pleurodesis?

Yes, but it’s uncommon. Talc pleurodesis works in 70 to 90% of cases. If it fails, it’s often because the lung can’t fully stick to the chest wall-common in advanced cancer or trapped lung. In those cases, an indwelling pleural catheter is the next step. Success rates with catheters are higher (85-90%) and they’re better for long-term control, even if the initial pleurodesis didn’t take.

Do I need to avoid certain activities after thoracentesis?

You should avoid heavy lifting or strenuous activity for 24 to 48 hours to reduce the risk of bleeding or pneumothorax. Light walking is encouraged to help your lung re-expand. If you have an indwelling catheter, you’ll get specific instructions on how to care for it and when you can shower or resume normal activities. Always follow your doctor’s advice based on your condition.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published.

8 Comments

This is one of the clearest breakdowns of pleural effusion I’ve ever read. Seriously, if you’re a med student or just someone dealing with this, save this post. The part about Light’s criteria and pleural manometry? Gold. I’ve seen too many docs skip the ultrasound and just wing it-this is exactly why we need better standards.

Light’s criteria is outdated. You’re still using 1972 tech when we’ve got proteomics and AI-driven fluid analysis now. If your hospital is still relying on LDH ratios and protein cutoffs, you’re behind. I’ve seen algorithms predict malignant effusion with 94% accuracy using just serum biomarkers and clinical history. Stop treating symptoms like it’s 1995.

Actually, Light’s criteria still holds up better than most new biomarkers in real-world settings. AI models need clean data and standardized labs-most community hospitals don’t have that. The real win here is indwelling catheters. I’ve had three cancer patients on them for over a year. One’s hiking in Colorado now. Quality of life isn’t a buzzword-it’s the goal.

While we're on the subject of evidence-based practice, I must emphasize that the 2019 ATS guidelines explicitly discourage pleurodesis in non-malignant effusions-yet I still see residents performing it like it's a rite of passage. The data is unequivocal: no benefit, high morbidity. And for heaven's sake, if you're not using pleural manometry during drainage, you're essentially gambling with re-expansion edema. 😒

Most people don’t realize that 30% of thoracenteses are unnecessary. You drain a tiny effusion because the radiologist said so and suddenly you’re in the hospital for a week. It’s profit driven. Insurance wants procedures done. Doctors don’t want to miss cancer so they overdo it. The real problem isn’t the fluid it’s the system

They say cancer causes 25-30% of effusions but what if its all just a lie? What if the real cause is 5G towers and CDC coverups? They dont want you to know that natural remedies like garlic and ozone therapy work better than chemo and catheters. They profit from your suffering. Ask yourself why they never mention detox protocols in this article

As someone from a country where access to ultrasound or even basic diagnostics is limited, I appreciate this level of detail. But I also know that for millions, the only option is to wait and hope. Maybe the real innovation isn’t just catheters or talc-it’s making these protocols accessible globally. Knowledge is power, but equity is justice.

The term "indwelling pleural catheters" is used with alarming frequency without proper contextualization. Furthermore, the assertion that patients report "better quality of life" lacks empirical substantiation from validated instruments such as the SF-36 or EQ-5D. The entire paragraph reads as promotional copy rather than clinical commentary. Also, "parapneumonic" is misspelled as "parapneumonic"-a trivial error, yet indicative of broader editorial negligence.