Adverse Event Rate Calculator

This calculator demonstrates how different metrics (Incidence Rate, Event Incidence Rate, and Exposure-Adjusted Incidence Rate) can produce very different safety results for clinical trials.

Key Insight: The FDA now recommends using exposure-adjusted metrics like EAIR for accurate safety reporting, especially in long-term trials where treatment duration varies.

This tool shows the mathematical differences between common adverse event metrics. It's designed to illustrate why the FDA's shift toward exposure-adjusted methods is critical for accurate safety assessment.

When you hear that a drug caused headaches in 15% of patients, it sounds simple. But what if one group took the drug for 3 months and another took it for 2 years? That 15% doesn’t tell the full story. In clinical trials, how you measure adverse events changes everything - and the FDA is pushing for better methods.

Why Simple Percentages Mislead

The most common way to report adverse events is the incidence rate (IR). It’s just the number of people who had an event divided by the total number of people in the study. If 15 out of 100 people got a rash, you say, "15% incidence." But here’s the problem: IR ignores how long people were exposed to the drug. In a trial where one group got the treatment for 6 weeks and another for 24 months, the longer-exposed group will naturally have more events - not because the drug is more dangerous, but because they had more time to experience side effects. A 2010 analysis found IR underestimates true risk by 18% to 37% in trials with uneven exposure times. That’s not just a small error - it’s a dangerous blind spot.Enter Patient-Years: The EIR Method

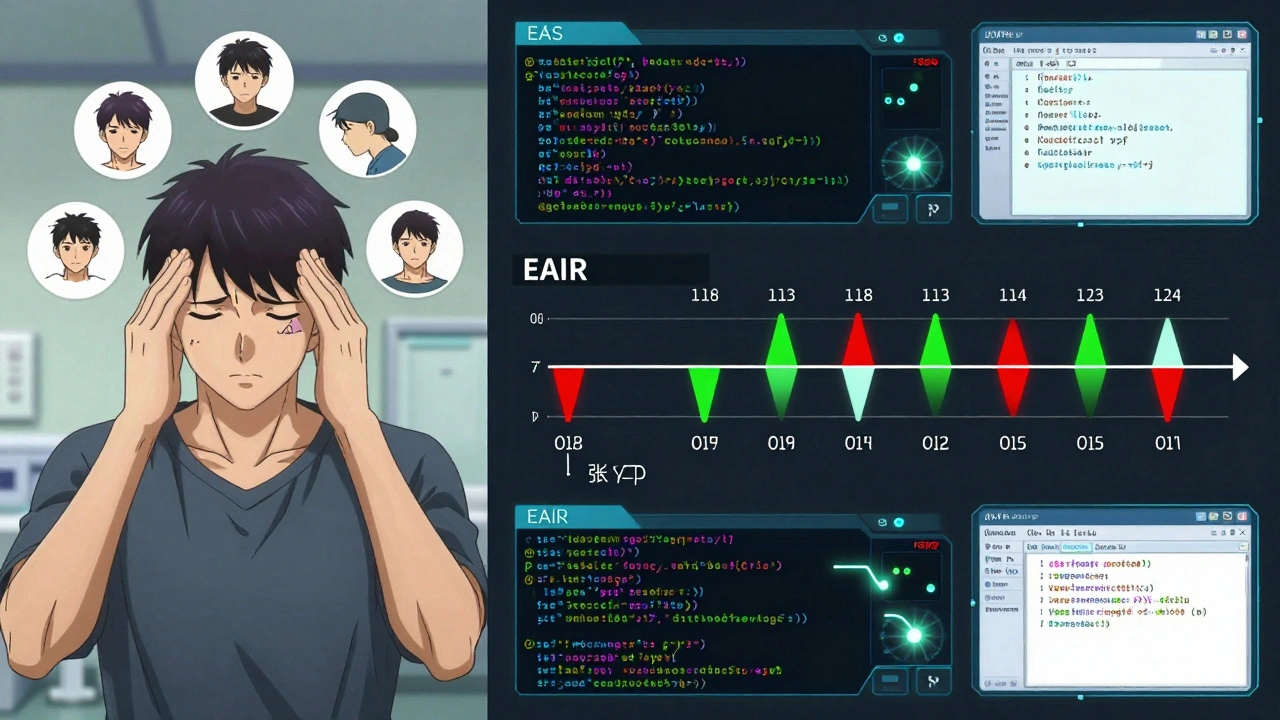

To fix this, statisticians started using event incidence rate adjusted by patient-years (EIR). Instead of counting people, you count time. One patient taking a drug for one year = one patient-year. If five patients each took the drug for 2 years, that’s 10 patient-years. If 15 adverse events happened across those 10 patient-years, the rate is 150 events per 100 patient-years. This method works well for recurring events - like nausea or dizziness - that happen more than once per person. It gives you a sense of frequency, not just who was affected. JMP Clinical and other regulatory tools now calculate EIR automatically using treatment start and end dates (TRTSDTM and TRTEDTM). But EIR has its own flaw: it counts events, not people. If one person gets 10 headaches, that’s 10 events. That inflates the rate, making the drug look riskier than it is for most users.The FDA’s New Standard: EAIR

In 2023, the FDA requested that a biologics company switch from IR to exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR) in a regulatory submission. That was a turning point. EAIR doesn’t just adjust for time - it also accounts for how many times an event occurs per person and handles treatment interruptions. EAIR is calculated by dividing the total number of events by the total exposure time, but with careful handling of when people stopped and restarted treatment. If someone drops out after 3 months, their exposure stops there. If they come back later, their time resumes. This matters because real patients don’t take drugs perfectly - they miss doses, pause treatment, or switch due to side effects. MSD’s safety team found that switching to EAIR uncovered safety signals in 12% of their chronic therapy programs that IR had missed. That’s not noise - that’s real risk hiding in plain sight.

Relative Risk and Why It’s Not Enough

You might think, "Just compare the rates between groups - that’s relative risk." But relative risk only works if both groups had the same exposure time. If Group A had 100 patient-years and 12 events (12 per 100 PY), and Group B had 200 patient-years and 20 events (10 per 100 PY), the relative risk is 1.2. But if you used IR instead - Group A: 12/50 = 24%, Group B: 20/50 = 40% - you’d say Group B had 67% higher risk. That’s wrong. The real difference is 20%, not 67%. The FDA and EMA now require clear justification for which method you use. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) E9(R1) guidelines, updated in 2020, say you must consider exposure time and treatment discontinuation. But they don’t tell you which formula to pick. That’s up to you - and your data.What the Industry Is Doing

The shift isn’t theoretical. In 2020, only 12% of FDA submissions included exposure-adjusted metrics. By 2023, that jumped to 47%. CDISC, the global standard for clinical data, now requires both IR and EAIR for serious adverse events in oncology trials (v3.0, 2023). The global clinical trial safety software market hit $1.84 billion in 2023 - growing at 22.7% a year - because companies can’t afford to get this wrong. But adoption isn’t smooth. A 2024 PhUSE survey found that 68% of companies now calculate EAIR alongside IR, but 42% ran into formatting problems when submitting to regulators. SAS programmers spent 3.2 times longer building EAIR analyses than IR ones. Common errors? Incorrect event dates (28%), ignoring treatment breaks (19%), and miscalculating patient-years (23%). Roche reported that 35% of medical reviewers didn’t understand EAIR at first. They thought higher numbers meant worse safety - not realizing it was just a rate per time unit. Training became essential.

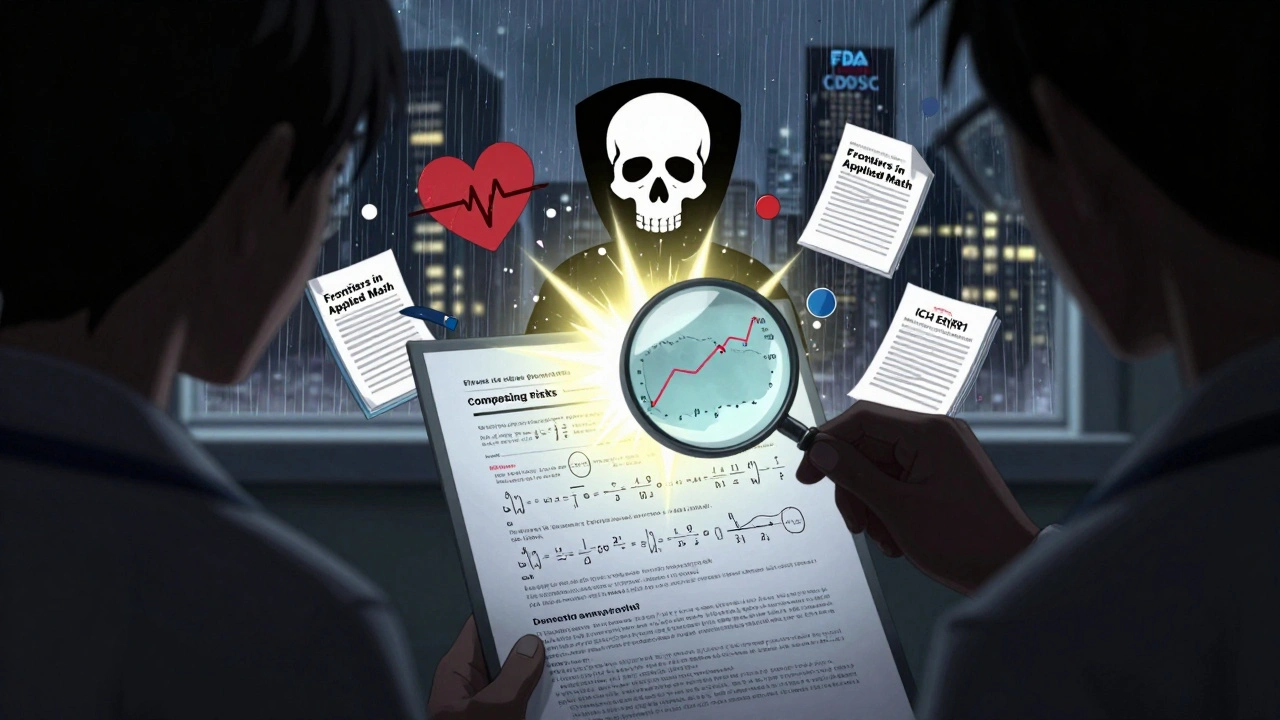

Competing Risks and the Hidden Danger

There’s another layer most people ignore: competing risks. If a patient dies before having a heart attack, you never see the heart attack. But if you use the standard Kaplan-Meier method to estimate risk, you treat death as if it’s just a lost observation - not a competing event. That inflates the estimated risk of the heart attack. A 2025 study in Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics showed that using cumulative hazard ratio estimation - which separates death from the event of interest - improved accuracy by 22% when competing events happened in more than 15% of cases. This isn’t niche math. It’s critical for drugs used in elderly or cancer patients, where death is a real possibility.What You Need to Know

- IR is simple but misleading if exposure times vary. Use it only for short-term trials with uniform dosing. - EIR is good for recurring events but overstates risk if one person has many events. - EAIR is the gold standard for long-term, complex trials. It accounts for time, recurrence, and interruptions. - Always justify your method. Regulators now expect it. - Use standardized tools. The PhUSE GitHub repo has free SAS macros that cut programming errors by 83%. - Train your team. If reviewers don’t understand EAIR, your data won’t get through.What’s Next?

The FDA’s 2024 draft guidance on exposure-adjusted analysis proposes a single, standardized EAIR formula. Public comments closed in October 2024. By 2027, experts predict 92% of Phase 3 submissions will include EAIR. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative is even building AI tools to auto-detect safety signals using these methods - with 38% better early detection than old systems. This isn’t about fancy statistics. It’s about getting the truth right. A drug that causes 10 headaches per 100 patient-years is very different from one that causes 10 headaches in 10 people over 3 months. One is manageable. The other is a red flag. The numbers matter. But only if you calculate them the right way.What’s the difference between incidence rate (IR) and exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR)?

Incidence rate (IR) is the percentage of people who had an adverse event, regardless of how long they were on the drug. Exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR) divides the total number of events by the total time all patients were exposed - accounting for how long each person was treated, including breaks and early stops. EAIR gives a true rate per unit of time, while IR can be misleading if treatment durations vary.

Why does the FDA prefer EAIR now?

The FDA prefers EAIR because it reflects real-world exposure. In long-term trials, patients often stay on drugs for years, miss doses, or stop early. IR ignores these variations and can under- or overstate risk. EAIR adjusts for actual time on treatment, making safety signals more accurate. The FDA formally requested EAIR in a 2023 submission, signaling a regulatory shift.

Can I still use simple percentages in my clinical trial report?

You can, but you’ll need to justify it. If your trial is short (under 6 months) and all patients had similar exposure times, IR may be acceptable. But for any long-term study, chronic therapy, or trial with variable dosing, regulators expect exposure-adjusted metrics. Submitting only IR risks delays or rejection.

What’s wrong with using Kaplan-Meier for adverse event analysis?

Kaplan-Meier treats events like death as "censored" - meaning it ignores them as if the patient just dropped out. But death is a competing event: if someone dies before having a heart attack, you never observe the heart attack. Using Kaplan-Meier in these cases inflates the estimated risk. For trials involving elderly or cancer patients, use cumulative hazard ratio methods instead.

How do I calculate patient-years for EAIR?

For each patient, subtract their first dose date from their last dose date, add one day, then divide by 365.25. That gives you patient-years. If they stopped treatment and restarted, add the separate exposure periods. Use treatment start (TRTSDTM) and end (TRTEDTM) dates from your SDTM dataset. Tools like JMP Clinical and SAS macros from PhUSE automate this.

Is EAIR required by law?

Not yet by law, but it’s becoming mandatory in practice. The ICH E9(R1) guideline requires exposure time to be considered in safety analysis. The FDA now expects EAIR for long-term trials, and CDISC mandates it for serious adverse events in oncology. If you don’t use EAIR when it’s appropriate, your submission may be questioned or rejected.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published.

15 Comments

Honestly? This is the kind of post that makes me glad I don’t work in pharma. But seriously, if you’re not using EAIR for long-term trials, you’re just gambling with patient safety.

IR is lazy. EIR is better, but EAIR? That’s the only way to stop regulators from calling your data ‘misleading’… and trust me, they will. I’ve seen it. Multiple times.

For anyone trying to implement EAIR: use the PhUSE SAS macros. They’re free, they’re documented, and they’ll save you 80% of the headache. Also-train your reviewers. I spent six months teaching my team that 150 events per 100 PY isn’t ‘catastrophic’-it’s just a rate. They thought we were killing patients.

Y’all are overcomplicating this. Just say: ‘We tracked time, not just people.’ Boom. Done. Stop hiding behind jargon. Real people don’t care about patient-years-they care if the drug makes them feel like garbage or not.

So let me get this straight… we’re spending millions to calculate how long people took a drug… because someone didn’t want to admit that 15% of people got headaches? Newsflash: people get headaches. It’s called life.

You know what’s really dangerous? The fact that this entire field is run by people who think ‘exposure-adjusted’ is a buzzword. The FDA’s pushing EAIR because they know the old methods are rigged. And guess what? The same companies that pushed IR for decades are now lobbying to keep it. Coincidence? I think not.

This is all a distraction. Big Pharma doesn’t care about accurate numbers-they care about getting the drug approved. EAIR? Just another way to bury the truth under math. If a drug causes 15% headaches, it’s toxic. No matter how you slice it.

The real question: why do we even measure this? Are we trying to cure people… or just satisfy the algorithm?

I appreciate the clarity here. The distinction between EIR and EAIR is subtle but critical. Especially when treatment interruptions are involved. I’ve reviewed submissions where they added up treatment days but forgot to exclude weekends. It’s not just math-it’s attention to detail.

To everyone stressing over EAIR: start small. Use the PhUSE macros. Run IR and EAIR side by side for one trial. Compare the numbers. You’ll be shocked. And then you’ll never go back. Trust me-I’ve been there.

There’s a deeper epistemological issue here: we’re treating adverse events as discrete data points when they’re emergent phenomena of human biology interacting with pharmacological agents. EAIR is a statistical band-aid on a system that fundamentally misunderstands the nature of harm. We need phenomenological models, not just exposure-adjusted ratios.

I’ve seen people panic when EAIR numbers go up. But if your drug causes 200 events per 100 patient-years, and your comparator is 50, you’ve got a real problem. Don’t hide from the data. Fix the drug.

Let’s be real: this isn’t about science. It’s about liability. Companies don’t want EAIR because it exposes how many people they’ve quietly harmed over years of ‘safe’ use. The FDA’s just catching up to the body count.

So EAIR fixes everything? What about patients who take the drug for 10 years and then die of old age? Do we count that as exposure? Or do we just pretend they never existed?

I work in oncology. EAIR isn’t optional here. One patient had 14 episodes of nausea over 18 months. IR would say ‘1 patient, 1 event.’ EAIR says ‘14 events per 1.5 patient-years.’ That’s not noise-that’s a signal. And if you miss it? You’re not just failing science. You’re failing patients.